Imprisoned New Orleans Rapper Mac Is Looking for Redemption

"I feel like I was born in prison."

McKinley Phipps, Jr. isn't complaining. The 37-year-old—better known as Mac, the New Orleans rapper who once played an integral role in Master P's No Limit Records empire—is merely stating a matter of fact. Mac has been locked up since 2001, when was convicted of manslaughter stemming from the shooting death of a young man in February 2000 and sentenced to 30 years in prison. But now, in light of a new investigation led by The Medill Justice Project that has cast serious doubt as to the veracity of key witness testimony, there's hope that Mac may be released, ending years of false imprisonment. Justice, he believes, might finally be served.

Mac is currently housed at the Elayn Hunt Correctional Center in St. Gabriel, La., a prison most notable for its mass cemetery bearing the graves of inmates whose remains are unclaimed by family or friends. Phone interviews with inmates at Hunt are difficult; they have to be conducted in 13-minute segments before a recorded voice cuts off each call. (At one point, XXL's communication with Mac is terminated after prison officials suspect a third party may have been patched into the conversation.) But Mac's disposition is sunny, almost impossibly so. "I just hope that this [renewed investigation] leads to the eventual outcome, which is having the truth come out," he says in a January phone call. "That's what I've been advocating since I came here: the truth. Hopefully all of this will shed some light on some things that happened."

The indisputable facts of the case are as follows: In February of 2000, a 19-year-old man named Barron Victor, Jr. was shot to death inside Club Mercedes in Slidell, La. Mac was there that night to help promote an open mic event. With him was his mother, Sheila Phipps, his father, McKinley Phipps, Sr. and a handful of friends and hangers-on. The rapper was arrested that night and charged with second-degree murder, defined in Louisiana in part as a killing that occurs when "the offender has a specific intent to kill or to inflict great bodily harm."

That night after the shooting, Mac and his entourage left Club Mercedes in several different vehicles. Shortly thereafter, police officers followed two members of Mac's security detail—who had been out looking for food—to the Phipps residence. The officers explained that there had been a shooting, that the victim had died and that Mac was under arrest; he remained in custody while the police's investigation proceeded. He was never released.

In his original statement to detectives, Mac initially had another theory as to the shooter's motives. According to the statement, the MC was observing the club, unsure as to whether he would perform due to a somewhat lackluster turnout. When he emerged from the bathroom, he witnessed a commotion near the front of the stage, then heard a shot ring out. "[W]hen the shot fired, I ducked, but all I seen is people running, running, running," he says. "My next move is, 'Like, okay, where in the hell is my mother?' You know, my mother is collecting [Mac's appearance fee] at the door. I'm thinking maybe there's some distraction, really, to try to get the money from my mom." From there, the interrogation spins in circles, the detective shutting down Mac's explanations by returning to the fact that two witnesses claimed they saw him with a gun.

The finer points of the investigation read like plot points in a Shakespearean comedy of errors. To start, a man named Thomas Williams confessed to the crime less than two weeks after it occurred. Williams, who was working security for Mac on the night of the shooting, turned himself in to the St. Tammany Sheriff's Office in the presence of his minister. Williams claimed that Victor had charged at him with a broken beer bottle and that he had acted in self-defense. (Williams' confession was dismissed at trial, as the St. Tammany Sheriff claimed it did not align with the physical evidence.)

The prosecution's chief eyewitness was the cousin of the deceased, a man named Nathaniel Tillison. Tillison claims he saw Mac fire shots into Victor at point-blank range; other witnesses in the club not only contradicted Tillison's account, but have also placed him in locations from which he would not have been able to see the shooting. Tillison said on the witness stand that Mac had hit a man in the head during a scuffle; in his initial statement to police, Tillison identified the aggressor as one of Mac's associates. He also claimed to a St. Tammany deputy to have seen another man with a gun, saying, "If Mac didn't do the shooting, you know who did."

The only other eyewitness to testify, a woman named Yulon James, admitted that she had not seen the actual shooting. In a 2013 affidavit, James said that St. Tammany law enforcement officials coerced her into pegging Mac as the shooter. Mac and his mother each feel that No Limit artists were being targeted by Louisiana law enforcement during the late 1990s; similarly, they share a belief that Mac was named as the shooter during the ensuing melee because he was the one identifiable face in a sea of chaos.

In light of weak testimony and a total lack of a forensic case, the prosecution honed in on Mac's claim to fame: his music. The Assistant District Attorney at the time not only read some of the lyrics from Mac's album Shell Shocked's "Murda, Murda, Kill, Kill," but told the jury that the rapper "chose to live those words." Mac's mother, on the other hand, has another explanation. "My husband was in the military, and in the Vietnam War," Mrs. Phipps says in a conversation with XXL. "So a lot of the things my son was rapping about were my husband's stories he used to tell."

Though there were firearms at the Phipps' residence—and on Mac's person—the night of his arrest, none of the ammunition matched that which had killed Victor. In fact, the murder weapon was never recovered. No physical evidence has ever connected Mac to the shooting. During deliberations, the jury asked the judge for clarification between second-degree murder and manslaughter. After a 7-hour wait, Mac was convicted of manslaughter in a 10-2 decision and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

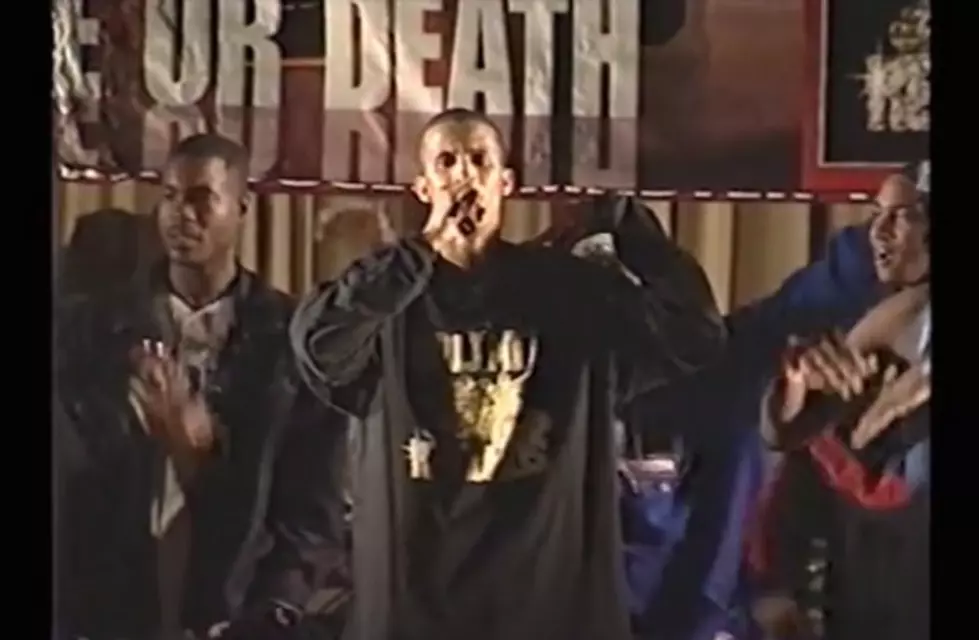

Mac was 24 years old when he got locked up, but at his peak he may have been New Orleans' finest rapper. Shell Shocked, his sophomore album, was his creative and commercial high-water mark. Released in 1998, the LP had all the hallmarks of a No Limit release: block-rattling instrumentals from Beats By The Pound, an endless string of features and a similarly expansive running time. But while a troubling number of records that came from Master P's golden conveyor belt were bloated and unfocused, Shell Shocked is fierce and dynamic. Master P, Silkk The Shocker, Mystikal, C-Murder and the late Soulja Slim, who shines on the standout "Can I Ball," contribute stellar turns, though none can crowd Mac out of the booth.

The most pronounced influence on Shell Shocked is actually far removed from Louisiana; like C-Murder, Mac borrowed liberally from 2pac's toolbox, especially with regard to the performative aspects of rapping. That Mac's DNA was infused with pieces of other regions was no accident. Since he began rapping in elementary school, he studied music from both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. "In my little mind, those East Coast guys were the real lyricists," Mac recalls. "I wanted to keep those Southern beats, because the beats were banging, but I wanted to hold myself to the standards of those guys in New York."

By the time of Shell Shocked's release, Mac had been a professional rapper for nearly a decade. A child prodigy, Mac landed a record in stores before his 13th birthday. "He entered this city-wide contest," his mother remembers. "The prize was a record deal and $500." She pauses, then cackles. "I didn't think he'd win. But, oh, he did." Officially pressed in 1990, but available locally the year before, his formal debut The Lyrical Midget was notable not only for its lead rapper's age, but for the contributions from a budding young producer named Mannie Fresh. Fresh, later the fulcrum for Cash Money Records' meteoric rise, acted as an early mentor and musical guide to young Mac, who briefly affixed a "Lil" to his stage name. "When Mannie Fresh would go to sleep, I would sneak and plug up his SB-1200 and try to bang on it," Mac remembers. "Eventually, he sat me down and showed me a few things just so I wouldn't break his equipment."

After letting that deal with Yo! Records lapse in 1992, Mac began making music with a series of local outfits. Nola legend Gregory D was an early believer in Mac, watching the youngster mastermind his neighborhood friends' rap and dance efforts when Mac was still in elementary school. That relationship put Mac on the radar of New York Incorporated, one of the two premier rap groups in New Orleans. Not content to follow in the footsteps of his elders, Mac helped found the Psychoward, an amorphous collective that he posited as an alternative to the rest of New Orleans hip-hop. "We were like the New Orleans version of Wu-Tang," Mac recalls.

All of these new connections—not to mention a song with No Limit's Kane & Abel—brought Mac to the attention of Master P. Though he was being courted by both Russell Simmons and Kevin Liles at the time, Mac opted to sign with No Limit and stay close to home. "As much as I like New York music, I don't think I was ready to move to New York," he says. "'It's cold, it's crowded, I don't know anybody out there, I'll be out there by myself like a fish out of water.' It was a decision I had to contemplate, but eventually I decided to stay around."

Shell Shocked was a rousing success, capitalizing on No Limit's distribution deal with Priority and debuting at No. 11 on the Billboard 200 album chart. Though his third album, World War III, didn't make quite the same impact, Mac parlayed his notoriety into a prominent role in the 504 Boyz, the No Limit supergroup consisting of him, Master P, Mystikal, Silkk The Shocker, Krazy and C-Murder. "Wobble Wobble," a single from their Gold-selling 2000 album Goodfellas, opens with a verse from Mac.

Just a few months before Barron Victor was shot, No Limit's in-house production team, Beats By The Pound, left the label over a dispute with Master P. The writing was on the wall. In 2000, Mystikal followed Beats off the label; three years later, No Limit Records had filed for bankruptcy.

Today, Mac's national profile is nearly non-existent. But he's far from forgotten in Louisiana; in 2009, a group of artists and activists came together to throw a benefit concert, donating 100 percent of the proceeds to the Phipps family's legal fund. At the time of the show, David "Dee-1" Augustine, a local artist and one of the event's chief organizers, wrote that Mac is like a big brother to him, citing his own tribute track, "Living Legend."

For her part, Mac's mother is grateful that her son's name still draws crowds in New Orleans, Baton Rouge and the rest of the state. And though she doesn't love to hear her sensitive son cursing on his records, she can't help but beam with pride at what she calls "the poetry in his work."

"If Mac wasn't my son," Mrs. Phipps says, "I think I'd be a fan."

"I'm like a power forward in denial," Mac says, laughing. "It's because of my height. In here, I have to play power forward, but I really like to roam around, so my true position is actually small forward." If he seems unnaturally jovial for a guy who's entering the second half of his second decade behind bars, that's because he is. Mac takes a tremendous amount of pride in his frequent basketball games. And not only is his demeanor a wake-up call to civilians, so is his time management.

When he's not stretching the floor, Mac is plying various trades around EHCC. "In Louisiana prisons, you're gonna work," he says. "For the past couple months, I've been an orderly in one of the departments here. I do some clerical work. I clean up, stuff like that." Most of his time, energy and meager resources, however, go toward music. Whenever possible, a close-knit "music club" rehearses, writes, and performs together inside the prison. "I've been at this particular facility for nine years," he says. "I've seen some changes, but this group of guys, we've been together for a good five or six years."

How often do inmates talk about time served as a measure of lineup stability? Mac handles keyboards and ("of course") vocals; beyond him, the club consists of three guitarists, two bass players and a pair of drummers. "Coming here, I gained a better knowledge of things I already knew how to do," he says. "I could play some instruments before I even understood what I was playing." Mac's mother echoes this sentiment, saying that her son has become a much more complete songwriter during his incarceration. He plans to continue writing and recording upon his release. "I can't ever stop," he says simply.

Through his incarceration, Mac has grown calmer, more centered. Even all the way back in 2004, while his conviction was still an open wound, he maintained in interviews that he and his family were "really trying to prove [his] innocence more than anything." Mac added at the time, "The [legal matters] will be secondary; we're really trying to prove my innocence." It's a philosophy he echoes now. Through dozens of completed or abandoned appeal attempts, Mac has been fixated on what he repeatedly calls "the truth"—that he did not kill Barron Victor, Jr. in a Louisiana club 15 years ago this month.

As for Sheila Phipps, she has dedicated her life to protecting those prisoners who believe that, like her son, they have been betrayed by the justice system. A lifelong artist ("I've always painted portraits to make extra money—I have all these kids!"), Sheila has taken to portraying men who have been convicted of crimes she believes they did not commit. When a family—or, as is often the case, an advocacy group like The Innocence Project—reaches out to her, she evaluates the case, then begins communicating with the accused. Sheila has displayed her work at prominent galleries and other spaces around the country; she is currently writing a book called A Family Behind Bars.

Just as her son has been resolute in the face of injustice, Sheila has approached the situation in the most thoughtful, empathetic way possible. "I'm sure if my son is in this situation, there are a whole lot of people in this situation," she says. "You've got to understand, before this happened to us, everybody who they said was guilty, we thought they were guilty. We believed in the system—we had no reason not to." Not anymore. At one point, a lawyer working on the case lamented to Mrs. Phipps that she doubted a judge was even reviewing her repeated appeals. Things seemed hopeless.

Now, the entire Phipps clan is optimistic. The Medill report has sparked a renewed public interest in Mac's case. Its chief legal value will be in its account of the investigation process, calling into question both the ethics and motives of the St. Tammany officials in the days and weeks following Victor's death. The most damaging thing, Mac believes, was his being physically removed from the legal proceedings while he awaited trial. Four of his bond applications were denied and he believes this severely handicapped his ability to work with his lawyers in an effective manner.

But now, Mac can nearly taste the fresh air. A scheduled release in 2024 is in the distance, but still-gestating plans for appeal are aiming to have him out sooner. And though he's 37 now and has at times worried about rapping at what the hip-hop world would consider an advanced age, those are momentary fears. "Some people are good at building houses," Mac says. "Some people are good plumbers. Some are doctors or lawyers. Well, hip-hop is what I do."

"I've always seen a light at the end of the tunnel," he says. "When you know something, it can be hard to get people to see what you know. I've had my moments where I've been discouraged. I've felt things are not happening as swiftly as possible. Wavering, faltering—that's gonna happen. But my confidence is always there. That's what keeps me sane in here."

He pauses, perhaps sensing how strange his outlook sounds given the circumstances. But his thesis is simple. "I always knew that the truth would come out," he says. "I know it's out there." —Paul Thompson

Related: New Investigation Reveals Mac Of The 504 Boyz May Be Innocent Of Manslaughter

The Stories Behind Master P's 10 Best Songs

Salute Me: 20 Years of No Limit Records

More From XXL