Nipsey Hussle On Major Labels: “We’ve Been Colonized; Hip-Hop Is Like Africa”

Nipsey Hussle has been on his grind for more than a half-decade now and he's seen his fair share of ups and downs in the music industry. After a series of successful mixtapes won him a major label deal with Epic Records and catapulted him onto XXL's 2010 Freshman list, he hit a road block that forced him to recalibrate his position within the industry. With his debut album on the shelf indefinitely, he left Epic and started out independent, resisting offers from Rick Ross' Maybach Music Group and other majors that came calling in order to craft his own way through the business.

Last week, that stance paid off in a big—and immediate—way, as he sold his new Crenshaw mixtape for $100 apiece at a pop-up shop in his hometown in California. He printed up 1,000 copies, and ended the evening devoid of CDs but with $100,000 in his pocket—$10,000 of which came from Jay Z, who had Roc-A-Fella purchase 100 copies alone on his behalf. Yesterday, Nip hopped on the phone with XXL to break down the idea behind selling a mixtape for $100, the support he's received from his fellow artists, why he believes that the major label music industry is colonizing hip-hop as if it were Africa and why he's on the forefront of a new school of artists looking to break the stranglehold of the music industry. —Dan Rys (@danrys)

How'd you come up with the idea to sell Crenshaw for $100?

It was a collective idea between me and my business partners. We all sit down every week and just bounce ideas around, sometimes we got crazy, way out ideas, and we just all throw them at each other and see how the group feels about it. Traditionally, I would just do regular mixtapes, put them on Datpiff, drop the mixtape, do videos to support it, and then tour as a form of promotion for the album, which is Victory Lap. We looked at my career, how many mixtapes I've dropped, and the level that that took us to, and we were just like, you know, we've done that already. And it's new music, so we just wanted to try to do something else, if nothing else than to make the people talk a bit.

"At worst, we just get a lot of publicity, and at best it's going to spark something off. And I think what happened was the latter.”

We didn't want to distribute it [as an album] because we don't want to impact our sales history to the point where people would look at our SoundScan and they'll judge us based on whatever this project does, and we didn't really go into it from the jump with the intention of making it a hot seller. So we didn't want to hurt ourselves in the future. So we were just like, let's print it up like a limited edition novelty game, kind of like with video games when you got the extra package that comes with the headset, you know, one of those types of things.

I had been reading a book about what makes people talk about things, what makes things go viral and what makes things contagious. There was an example in this book about a restaurant owner who made a $100 cheesesteak. It made some people mad, say, "Who does he think he is, selling a sandwich that other people sell for $4 for $100?" Then you also had the people like, "Well, what does this sandwich taste like? Why does it cost $100? What makes it so good?" It made some people curious, it made other people upset, but more than anything it created conversation. And he ended up on the Oprah show, and he ended up on David Letterman talking about this $100 cheesesteak.

We wanted to make sure we justified that price, so we came up with the Proud2Pay concert idea. It's a concert that the average fan can't buy tickets the day of, you have to buy the product. And this is strictly for people who bought into the idea of Proud2Pay, fuck the middleman, that idea. Once we got to that point with the conversation, we just started bouncing ideas about how we could keep this engagement going—we could do cool shit like call their phone and say thank you, or the first person who bought it could ride around all day with us and get the first hand experience, and number 350 might randomly get a letter to his house with a signed, one-on-one picture, or we might give out my old rap notebook from the 7th grade, I'll find it and sign my old rap notebook. It's a different level of connection between those people that felt the music and believed in the brand to the point that they spent 10 times the price they'd usually spend for a product. At worst, we just get a lot of publicity, and at best it's going to spark something off. And I think what happened was the latter.

What was the scene like at the pop-up shop that night?

It was cool, man. Ross sent a box of Belaire champagne, so we was all just drinking champagne, playing music. It was all love—it felt like a family reunion. I really felt like everybody in the store had heard every word that I'd ever put on wax. I felt like they'd heard every rap of mine, every message I'd put in my music. Everything was cool, the new album was playing, it was the first time they'd heard it, because it hadn't gotten released on Datpiff until the next day. So they got to hear it first, I got to watch them react to it. It was dope, man, I'd never done that.

Some of my peers came through—Glasses Malone came through and bought the album, the LA Leakers came through, Dom Kennedy came through. It was cool, man. We'd done meet and greets, but this was a little more exciting, with the music being fresh and everybody there knew they were a part of history. I think they respect that I stayed independent, that I almost sacrificed myself for what I believed in. I believe that we should own the fruits of our labor and the assets of our creations. At one point it was looking like, you know, I was hurting myself for standing so solid on my beliefs. Why didn't I sign to MMG, or do a deal; everybody always knew there were deals on the table. But I think they were proud of me, that I stuck to my guns. When the message came clear that this was what I was doing, they supported that. So it was dope, on a lot of levels.

You said the other day that you think that the major label music industry, for the most part at least, is a dead industry. Chance the Rapper said the same thing, and he's another who has resisted the offers of labels. What do you think the industry is going to morph into?

Music is always going to be present in our lives; we need it to live. I think there will always be people who stand to gain from this economy around music. But I think that the business model that these major, giant companies are attached to, I think that if they don't adapt, they're gonna end up like Blockbuster. Like Tower Records, in a warehouse. We've seen it happen; it's an arrogant business model. Because when you get an artist like Nipsey Hussle at the table and he's telling you, "Look man, let me be involved in ownership, it's gonna cost you the same amount of money, I don't want a check up front, I just need production, marketing, distribution and access to your network of retail." And we're at the table and they're arrogant enough to let me walk out, tell me that they'll write me a check but that I can't have no ownership. That's not how we work, that's not how we operate. That's the reason they're gonna turn into Blockbuster. And we're gonna be Netflix. When I say we, I mean the new generation of artists. They're gonna create their own business models, and we're gonna give up this idea of super-sized celebrity, and we're just gonna get back down to the bottom line of doing what we love and getting paid for it.

"I'm personally offended by the business models of these major labels...and I feel like the culture should be offended. We should give all the labels the boot, and tell them we don't want them no more unless they get their mind right.”

Who else would you say is in that new generation of artists alongside you?

Dom Kennedy, Curren$y. I think Wiz Khalifa—even though he's on a major label, he built his situation outside of the majors first, which gave him a unique situation. A lot of these artists coming up after us—especially with what just happened with this Crenshaw thing—I think the game has reset. It's now, make a hot mixtape, be a good artist, and also having an innovative business model is now a requisite.

What's the biggest thing you've learned from this experience?

Honestly, not to sound arrogant, but I think I proved what I had been trying to scream out for the last couple years, or at least took a step toward proving it. I think that a demonstration on a small level in the battle, the war that we're fighting, it represents a win. It's like David and Goliath to an extent. They threaten artists—you're gonna become irrelevant, you better sign, you can't do it without us—whether they do it overtly or not, that's the relationship. It's like, well, go ahead and do it on your own, but I hope you got a million dollars to promote yourself, because you can't compete with us at radio, you can't get your shit in chain stores because you don't have the relationships. It's an arrogant stance, and this is our culture. It's like we've been colonized. Hip-hop is like Africa right now; our natural resources, we're watching them get taken from us. The people that control and own the lion's share of the assets aren't indigenous to the culture at all. It ain't about white or black or race, it's about love for the culture of hip-hop. I just feel like things are necessary, things like this have to happen, or we're gonna end up raped. We're gonna end up like other genres. And then the people move on.

I feel like hip-hop is the culture of the world right now. I've been to every country, and I've seen it—they may not speak English, but they know who 50 Cent is, they know who Jay Z is, they know Tupac. I was in a remote part of Africa, and they got Tupac tacked on the wall. That showed me the power of hip-hop culture. And the natural resource—the pain, the struggle, the story—I think the people that are indigenous to that should have some control, or some stake in it. I'm personally offended by the business models of these major labels. When you walk in with an artist with a built brand, a built fanbase, who understands what he wants, and you say you can't do it, but you can cut me a check? I'm offended, and I feel like the culture should be offended. We should give all the labels the boot, and tell them we don't want them no more unless they get their mind right.

What else have you been working on? I know you got Victory Lap on deck.

Yeah, you know, that's like the Detox of my catalog. [Laughs] There's more of a vision for that project, but it is a time thing. I think that's another thing with hip-hop artists; we're under scrutiny as far as how long it takes us to do this. If we wanna have timeless projects that live forever—I wanna make a Dark Side of the Moon, I wanna make an Adele, 21-type album, at least once in my career—I wanna have one of them where you can look on the charts and see it in the Top 40 in history. I think hip-hop can do that. One of the things that will stop us is having these time restrictions and these social pressures of being in the marketplace every six, seven months or else you ain't hot anymore, or you fell off. I think it just takes somebody secure enough in themselves who can withstand the social pressure and just stick to their guns, and that's what I'm doing with Victory Lap.

When it's ready, I'm gonna give it to the people, and until them I'm gonna keep feeding them with music just so that the people that are out in the barbershops arguing for me, out in the streets arguing for me, just so I can give them ammo. That's why I'm gonna stay in the marketplace, just for them. Not for the people that say, "Oh, he's hot." None of that shit. My brand evangelists, the ones that are out here fighting for me, they already know. They're fighting for me, and I'm gonna give them that ammo. I don't want them out there with empty guns anymore.

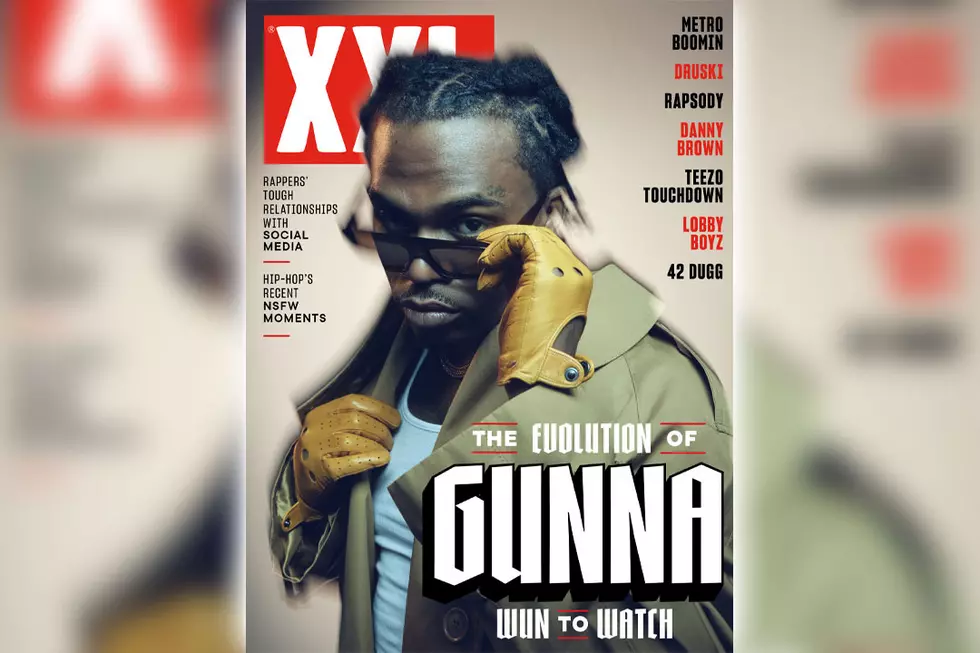

More From XXL