![“Book of Rhymes” [May 2011 Magazine Excerpt]](http://townsquare.media/site/812/files/2011/04/eminemfeature1.jpg?w=980&q=75)

“Book of Rhymes” [May 2011 Magazine Excerpt]

WORDS BEN DETRICK

**THIS STORY ORIGINALLY APPEARS IN THE MAY 2011 ISSUE OF XXL ON SALE NOW**

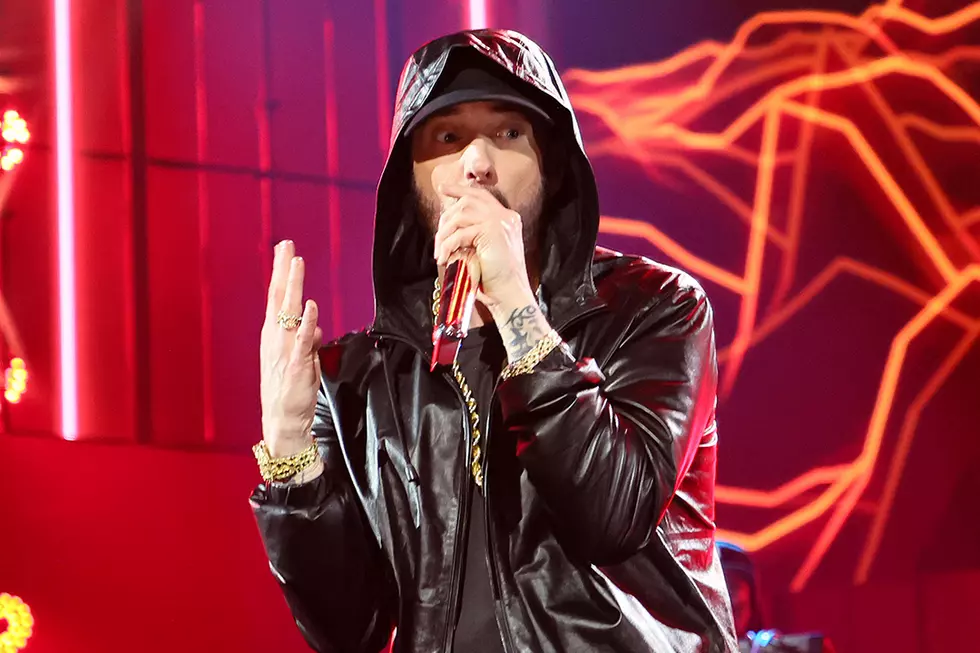

Once a cherished part of a rapper’s arsenal, the rhyme book has been gradually sliding toward irrelevance. In part, the diminishing importance of the notepad is due to technology—a fate mirrored by that of vinyl, books and other “hard-copy” artistic mediums—but also because of changing attitudes, rhyme techniques and production values within hip-hop itself. As more and more rappers compose rhymes in their heads or on smart phones and computers, we—rap fans, journalists, documentarians—are steadily losing our ability to investigate the process that goes into lyric writing. Just as there’s inherent value in viewing Picasso’s sketches or Kerouac’s original manuscript for his 1957 novel, On the Road, typed on a 120-foot scroll of paper, it’s fascinating to look at Eminem’s handwritten rhymes—made so famous in his semiautobiographical 2002 movie, 8 Mile, and the March 2004 XXL photo shoot that displayed them—and see how Eminem intertwines couplets into dense, witty verses. But beyond such scholarly pursuits, it must be asked: Is rap’s abandonment of the rhyme book affecting the music?

Hip-hop may have evolved as the displaced descendant of African oral tradition, but the written word got involved early. In 1979, when Sugarhill Gang released the nascent genre’s breakout hit, “Rapper’s Delight,” the track included verses Big Bank Hank plucked from Grandmaster Caz’s collection of written rhymes. “When Hank said he needed something to say, I whipped out a book,” says Caz, who never received royalties for writing the lyrics. “The rest is history.” The single became one of the most famous rap songs ever made, and the importance of the notebook was stitched right into its lore.

For many rappers who came of age during the 1980s, having a well-stocked rhyme book was an indication of an artist who took his or her craft seriously. Just as graffiti writers used their “piece books” to plan out designs before they sprayed them on subway cars, rappers used their notebooks to catch the inspiration when it came and to perfect their creations for performance. Like Nas said on his 1994 track “The World Is Yours,” “I sip the Dom P/Watchin’ Ghandi ’til I’m charged/Then writin’ in my book of rhymes/All the words pass the margin.” Some became so attached to their books that they’d carry them with them wherever they’d go. “When I was young, I used to run with a notepad,” Sadat X rapped on Brand Nubian’s 1992 single “Punks Jump Up to Get Beat Down.”

Early in his career, Rakim, the artist credited with modernizing rap via the complexity of his lyrics, misplaced a full rhyme book and spent months worrying that it had fallen into the wrong hands. As a safety precaution, he began writing rhymes in wild-style graffiti lettering—a fact he later alluded to on the 1990 single “Let the Rhythm Hit ’Em.” “I figured if I lost it, no one would be able to [decode] it,” he says. Rakim believes the use of a notebook is intrinsically tied to thoughtfulness and a deeper commitment to the writing process. “It stands for consciousness in hip-hop,” he says. “If you sit down, it means you’re going to put in time. It’s really important for the culture, and it definitely shows substance.”

**TO READ THE REST OF XXL's BOOK OF RHYMES STORY, PICK UP THE MAY 2011 ISSUE OF XXL. ON SALE NOW.**

More From XXL