Lil Wayne

Money In The Bank

Champions, it is said, are not made. They are born. Still, there are times when people seem to speak things into existence. Take the boxing legend Cassius Clay, better known as Muhammad Ali or, simply, “The Greatest.” Certainly, his achievements—his Olympic gold medal (Rome 1960), his professional record (56-5 with 37 KOs), his three times winning the heavyweight championship of the world—speak to great natural ability in the ring. But his status in history probably has more to do with his overflowing well of charisma and bravado. Ali is the greatest for one overriding reason—he told us he was. Repeatedly. And we believed him. Not at first, but eventually, because his actions lent truth to his words.

Lil Wayne, born D’Wayne Carter in New Orleans in 1982, finds himself at a similar point in his career. Originally perceived as just another materialistic MC from the South, the Cash Money Records star has spent the past few years building a strong case for being the “best rapper alive, since the best rapper retired” (a reference to Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter, no relation). Initially uttered on the closing refrain of his 2004 hit “Bring It Back,” the statement raised its fair share of eyebrows. By the end of the following year, Wayne had upped the ante and flat out said he was the “best rapper alive.” Period.

Yeah, the kid has an impressive scorecard—over five million units sold as a solo artist, another two million counting his work with Juvenile, B.G. and Turk as a part of Cash Money’s since-splintered supergroup the Hot Boys—and his skills have grown considerably since his start as a young teen. But to claim he’s the best? Surely someone twisted his locks too tight.

However, after a marathon 2006 that saw Wayne’s critically acclaimed fifth solo album, Tha Carter 2 (released in late ’05), top a million in sales (while most rap albums could barely crack 200,000), two stellar Gangsta Grillz mixtapes with DJ Drama, a gold-selling collaborative effort with Cash Money co-founder Brian “Baby” Williams and a slew of standout guest appearances, naysayers are beginning to sing a new tune. Through pure grit and determination, the kid called Weezy has positioned himself as a franchise player/coach at the label that raised him and has finally earned respect as a lyricist in hip-hop circles. He even snagged the highly coveted No. 1 spot on XXL’s 10 Most Anticipated Albums of 2007 list—Tha Carter 3 is tentatively due this summer. Those proclamations of greatness aren’t sounding so outlandish anymore.

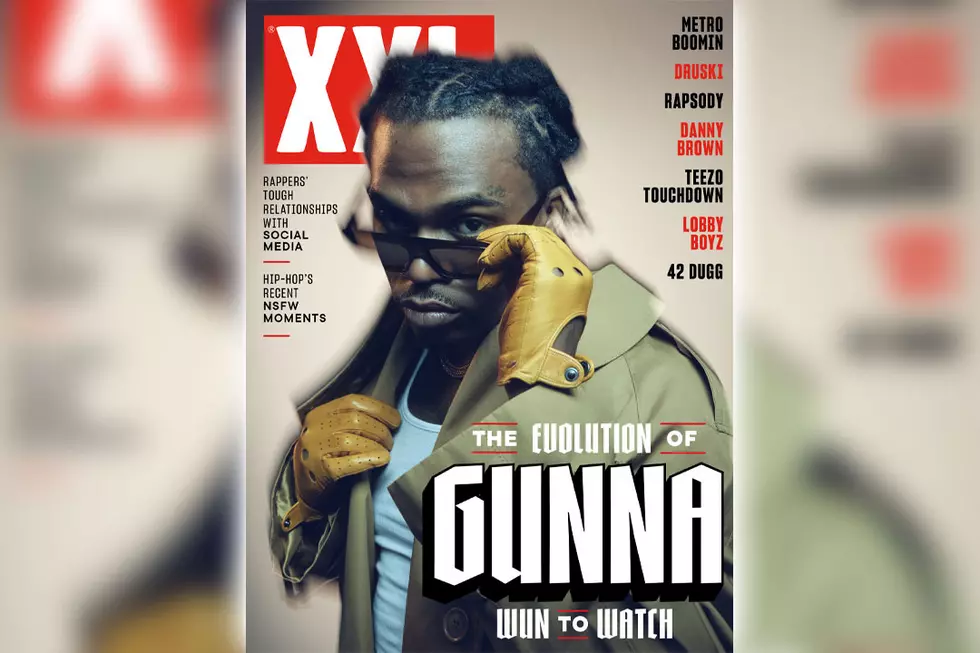

With that in mind, it seems fitting that Wayne would return to his hometown of New Orleans on this early January afternoon to re-create a famous photo of Ali surrounded by $1 million in cold, hard cash. (The image originally appeared in the Feb. 24, 1964, issue of Sports Illustrated). After baking under the photographer’s persistent flash, Wayne invited XXL onto his tour bus to talk. Speaking openly and easily (putting to rest recent rumors that his jaw had been broken in a fist fight), he gave us his take on his upgrade in artistry, his resurgence in popularity, Hot Boys love lost, Cash Money love lasting, why he’s still better than your favorite rapper and what lies in the heart of a champion.

You displayed a dramatic maturation in style between your 2002 album 500 Degreez and the first in your Tha Carter series in 2004. Can you explain how that transition came about?

Ain’t no transition. I ain’t worried about what people realizing, ’cause if I start worrying about when they gon’ realize, then I’d be crazy. It ain’t about that. I told you who I am. I’m the nigga that creatively do the stuff I want and make y’all realize it. And I don’t give a fuck if y’all realize it or not. I’ma keep doing me. That’s what I am, that’s who I am and that’s why I’m the best.

There has to be more to it, though. How’d you get so good so fast? What about people saying you got better because Gillie the Kid was ghostwriting for you?

There has to be more to it, though. How’d you get so good so fast? What about people saying you got better because Gillie the Kid was ghostwriting for you?

Who that is?

You know, the dude from Philly who was signed to Cash Money for a little bit. He says he used to write for you.

[Laughs] I don’t get it. How you could write for me and I don’t write? I’m rich as a muthafucka, and you wrote for me? Then why aren’t you rich? If I wrote for a nigga and this nigga’s on top of the world right now, I’d be like, “Where’s my fuckin’ money? Where’s my benefits?” I heard this nigga do an interview and say he got like $30 thousand a song. Show me one of them $30 thousand checks you got from writing for me. Show me, ’cause I don’t know what you wrote for me. I don’t write nothing, dawg. The only time I touch the pad is for someone else.

But something had to have changed, ’cause you weren’t rapping like this back in the Hot Boys era.

Oh, yeah. When everything fell apart, I had to become that. Coach let me know we lost a lot of players from the team, a lot of players got traded. “You know what you gotta do this year. The ball is in your hands. What are you gonna do?” That was the transition right there.

Mannie Fresh left the fold, too, in 2005. In hindsight, how does the departure of your label’s in-house producer affect your work?

It’s different for me, of course, because I’m rapping on different beats, and I gotta come up with different melodies, different subjects, and that kind of stuff. But it’s better, because you’re not hearing the same me. My old albums would be all put in one category. I don’t care if I had a song about saving the world, a song about shake your ass, a song about my jewelry, I’m killing, whatever—it was all one category, ’cause it was one sound. Now I think it makes it better, because if I wanna similar voice or certain opinion about a certain situation, I can get a different producer that can get that point across.

Cash Money was like a family, though. It had to be painful for you to see everybody leave.

I been shot twice—that’s pain. Anything that ain’t physical is not pain for me. Pain has a definition in the dictionary. Like when a muthafucka says, “I hate you,” and you say, “Oh, that hurted.” But that don’t fit that definition. Bow! Bow! That hurt. That’s pain. A nigga walkin’ away can’t hurt me.

What about reports that you got into a fight with somebody in your entourage recently and got your jaw broken? Something like that has gotta hurt.

[Laughs] Nah, man ain’t nobody break my fuckin’ jaw. Come on, man, you gotta break everything else after that, dawg. You ain’t gon’ hear that. You gon’ hear Lil Wayne dead. ’Cause you ain’t gon’ break my jaw and I’ma just leave it like that. It’s gon’ be, “What happened to the nigga who broke his jaw? He gone? Shiiiiiieeeeet.” I got $100 thousand worth of work up in this muthafucka. If you broke my jaw, nigga, you done broke the bank.

You caused a bit of controversy a few months back when you were quoted in Complex magazine saying that you’re better than Jay-Z. How’d you go from “best rapper alive, since the best rapper retired” to being better than him?

I’m glad you brought that up, ’cause I wanna apologize to Jay and his family and friends, because I was asked that question and they put it in there like I was just feeling like, “Oh, you know what, nigga? I’m better than Jay!” They came at me like, “So you say you’re the best. Can you say that you’re better than everybody? Would you say you’re better than Jay?” I was like, “Yeah, nigga, I’m better than everybody!” But I’d like to throw that apology out there ’cause of whatever trouble I caused, I ain’t want that to happen.

-------

Read the rest of our interview with Lil Wayne in XXL’s April 2007 issue (#90)

Read the rest of our interview with Lil Wayne in XXL’s April 2007 issue (#90)

More From XXL