Rick Ross And Maybach Music Group Are As Real As It Gets

Is Rick Ross fake? It doesn't matter. His music, his money and his growing empire are all as real as it gets.

Words: Ben Detrick

Images: Travis Shinn

“WE NEED TO GET IN THERE BEFORE THEY GET TO US.” RED, RICK ROSS’S SECURITY CHIEF, A MAN WITH THE SHOULDERS OF A LINEBACKER, SPEAKS AS IF THE RAPPER’S tour bus were being swarmed by fl esh-starved zombies. It’s 3 a.m. on a Saturday night, and the enormous vehicle has pulled up behind Club Adrianna’s, a nightclub outside of Chicago. This kind of place can be perilous for visiting rappers, a fact underscored by the 2006 shooting of T.I.’s friend Philant Johnson after a similar appearance in Cincinnati. As Ross and his entourage are shepherded through a back entrance by hulking club security personnel, people in the crowd shout “Rozay!” and mimic the rapper’s signature deep-bellied grunt. By the time the convoy cleanses several rooms of locals and shoves through a mobbed mezzanine, the DJ has shifted into a set of Ross’s hits. Finally deposited in a private area, Ross is presented with bottles of Champagne and sparklers. The crowd crushes inward, looking for photo opportunities and handshakes. A sequoia-sized member of Ross’s crew stands sentinel, scanning the sea of faces for anyone whose expression is a little too excited or icy. Wearing a black nylon jacket and his ever-present sunglasses, Ross is at home in the swirl of chaos. At this moment, he is exactly what he has always wanted to be: a rap star who performs in front of thousands but still gets love in the hood.

Later on, back on the bus, after a frenzied extraction, the 35-year-old rapper launches into an animated, 30-minute paean to his own authenticity. “There was five different gangs in that room,” he says, grabbing a handrail as the bus curls through the Illinois darkness. “Crips. Folks. You don’t see these other tough-guy rappers there. Check their tour schedule. They don’t go to Detroit, to Chicago. That’s the difference.” The spiel includes talk of his murderous Miami mentor, meeting with Larry Hoover’s son and the foulness of snitches. He even threatens Kreayshawn, the fledgling Bay Area rapper who called Ross “fake” in a recent freestyle verse. “I can’t wait to slap the shit out of whoever carries her bags,” he says with a sneer. “And I hope it’s her nigga. Dirty bitch. You better know who the fuck you talking about. I’ll pay 50K to mess up your whole week."

If the last year has proven anything, it’s that Rick Ross should not be concerned about his credibility. Despite a number of issues that could have doomed an inferior artist—the discovery that he worked as a correctional offi cer in Florida’s Dade County, an embarrassing ex-girlfriend who pranced around New York City with his rival 50 Cent, a lingering perception that his persona as a cocaine baron was overblown—he has risen to greater stardom than ever before. His last album, 2010’s Teflon Don, was critically lauded and spawned monster hits like “B.M.F. (Blowin’ Money Fast)” and “Aston Martin Music.” Ashes to Ashes, a follow-up mixtape, yielded more of the same with “John Doe” and “9 Piece.” He made high-profile cameos on tracks with Drake, Kanye West and Lil Wayne. He assembled a divergent group of artists for his Maybach Music Group label and, in May, elevated their stature with the compilation album MMG Presents: Self Made, Vol. 1. Squabbles with other rappers (Kreayshawn notwithstanding) and questions about his past are old news. With his fifth album, God Forgives, I Don’t, scheduled to come out this fall, Ross has his pudgy toes on the precipice of greatness.

“I’m enjoying my last few moments at No. 2,” Ross says, sitting on the bed in the back of his tour bus. “It’s like I’m watching the No. 1 man on stage, my legs crossed, I’m smoking big, hollering at the bitches in the crowd. And this album gonna do it. I got the formula.” His sunglasses are off , and his eyes are heavily lidded but alive. “Everybody on my dick,” he says, “like they supposed to be.”

The First Midwest Bank Amphitheatre, a concert venue about 30 minutes outside of Chicago, has towering support pillars and an ugly roof, which provide all the ambiance of a freeway overpass. After an afternoon of rain and hail, skies clear up in time for performances from Ross, Lil Wayne, Keri Hilson and Far East Movement. The sprawling crowd is a snapshot of the rap audience in 2011: kids with braids throwing up gang signs, frat bros in Hollister shirts, groupies in shrink-wrapped dresses and teenyboppers wearing hoodies emblazoned with “Love Pink.” And there is Ross, leading this weird congregation in chants of “I think I’m Big Meech.” He bounces along the catwalk, hunched down, his chin tucked into his chest. It looks a bit like a turtle trying to get off of a hot plate. “Took me 10 years to stand right here,” he announces to acknowledging applause. As Ross polishes off a set that includes hits like “Hustlin’ ” and “I’m on One,” steam rises from his bald, sweat-sheened head. Walking backstage, he yanks off his shirt.

For a man of significant huskiness, Ross is not bashful. Whether performing, during photo shoots or in the privacy of his trailer, he strips off his tent-sized tees with the casual exhibitionism of a sunbathing Frenchwoman. The folds of his upper body are a maze of tattoos—he says he has more than 100. Abraham Lincoln and George Washington are inked on his chest. The Statue of Liberty and Richard Pryor on his abdomen. On his right thigh is a portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat, the New York City painter, who died in 1988 of a heroin overdose. Basquiat, who did the cover art for Rammellzee and K-Rob’s “Beat Bop” in 1983, has become a popular name-drop among rap’s aspiring art appreciators; Jay-Z, Nas and Swizz Beatz have all made their admiration known. Ross doesn’t say much about Basquiat’s actual work, but he is enamored of his storied rise from homeless obscurity to the top of the art world. “I connected to that totally,” Ross says. “Just chasing his dream. It wasn’t about how much knowledge he had or who he knew. It was just his talent. And that’s what it was with me.”

Born William Leonard Roberts II in Mississippi, Ross was raised in Carol City, Florida, an area afflicted by grim poverty. Ross and his sister grew up living with their mother, who worked multiple jobs, the most prestigious being a nurse. Ross wandered into trouble as a kid, getting into the habit of breaking into houses, and paid a harsh price when people robbed his family’s home and torched it in retaliation. It was an awful truth to conceal. He, his mother and his sister were forced to move into a single motel room. When asked how long they stayed in those suffocating quarters, he exhales loudly. “It was a good little minute,” he says, staring into space. “Fuck. That shit was the worst.”

Hip-hop offered an escape from such desperate surroundings. As a kid, Ross wrote lyrics and listened to rap, ranging from A Tribe Called Quest to Tela to Raekwon, on his knockoff Sony Sport Walkman. In music videos were glimpses of places that occasionally resembled what he witnessed from his own window. “When I saw Eric B. and Rakim walking through the grimy-ass streets of New York, it was like, Damn, that’s the kind of shit I live in,” he says. “I used to love Ice Cube when I saw them niggas driving jeep Isuzus through the ghetto with curly perms. I felt they struggle. Those were the niggas I looked up to. For me to idolize you, you had to first start with nothing. You had to live in the conditions we were living in—that way it was fair grounds.” There were also promises of a better life. “Muthafuckas where I came from were always mean, mad, upset, crazy, hair nappy, dreads and shit,” he says. “Me listening to The Great Adventures of Slick Rick, seeing muthafuckas in good moods, telling stories—I was blowed away. I remember Cool C and the Hilltop Hustlers. I remember them niggas wearing Bally’s and silk suits, [thinking,] Damn, that’s how I wanted to dress right there.”

Most rap listeners were introduced to Ross when his anthemic 2006 single “Hustlin’ ” broke nationally, but the title of the track applies as much to his rap career as it does to distributing cocaine with “the real Noriega.” In an era when a teenager with skinny jeans can post up a video on Tumblr and rack up a million YouTube views in a week, Ross is a member of an older caste that plowed barren dirt for years without seeing much in return. He boasts of being rich without rap, but his résumé reflects someone deeply dedicated to fi nding a toehold in the hip-hop game. In 2000, he signed with Tony Draper’s Suave House label, a deal he now calls “the most fucked-up record deal in the history of the music business”; his debut album, Rise to Power, was put on hold. Later, Ross linked up with Jazze Pha and recorded in peripheral studio spaces while artists like T.I. and 8Ball & MJG worked in the main rooms. He signed with Slip-N-Slide in 2002 and ghostwrote lyrics for Trina. It was a frustrating time. “It took me longer than a lot of muthafuckas,” says Ross. “I was running around the industry, writing songs here and there for different muthafuckas who heard I was lyrical, but coming from a space where they ain’t really know what to do with me in Miami.” Once, when Ross learned reps from Atlantic Records were in town, he was confident his time had come. “Yo, they signed Pretty Ricky,” he says, shaking his head. “What the fuck? Okay, I wish y’all little niggas much success, but I’m fi nna show these muthafuckas. I’ma punish the game. That was my inspiration.”

When Rick Ross finally got his chance, he didn’t squander it. Led by the singles “Hustlin’ ” and “Push It,” his 2006 debut album, Port of Miami, sold almost one million copies and established him as a leading fi gure in the burgeoning coke-rap genre. His second album, 2008’s Trilla, sold another 750,000-plus units and yielded a single with T-Pain, “The Boss,” that still stands as his biggest mainstream hit. Amid a scandal touched off by photos that proved he had worked as a correctional offi cer, and a flurry of taunts from 50 Cent, the following year’s Deeper Than Rap fared less well. But it was his most artistically adept album up to that point, earning some strong reviews, and was, in retrospect, an indication of what was to come.

The elevation of Ross’s stature during the last year can be attributed to the most simple of reasons: He has been making thrilling music. Some recent hits from Tefl on Don—like “I’m Not a Star” or “MC Hammer”—are insistent bundles of ricocheting snares, nasty synths and declarative hooks. These records are punctuated with grunts and hoots, ad-libs that have become key components of the Rozay aesthetic. In July, Atlanta’s Yung Joc even dropped “Ugh,” a song built around Ross’s sonic calling card. “I been to performances, and they want those more than the lyrics,” Ross says. “They want that ‘Hunngh!’” But other records convey a lushly layered, almost orchestral musicality. There is depth—emotional and sonic—to Tefl on Don that Ross had only hinted at on his earlier albums. He has improved at songwriting and constructing cohesive albums, while branding Maybach Music’s sound as simultaneously aggressive and soulful.

Regarded by the cognoscenti as a one-trick pony for much of his career, Ross has finally begun receiving critical acclaim. One New York Times critic ranked Tefl on Don as the best album of 2010. Pitchfork.com, the notoriously picky music site, gave it an excellent 8.0/10 and wrote, “Sometimes a guy who was underrated, underappreciated and even considered a joke… generates so much momentum they eventually become undeniable.” On God Forgives, I Don’t, Ross is planning tom duplicate the feat. It will be another short, “highly concentrated” album, he says, reminiscent of his last eff ort. “When I make music, I go back to my late nights of me by myself, listening to Curtis Mayfield or R. Kelly’s 12 Play. There’s certain depths that music can take you to. There’s certain feels that you need to have. When you get to the last song on the album, I want you to have that feeling of being whole. I want to give these muthafuckas classic joints. That means more to me than anything else.”

For all of Ross’s omnipresence on the streets, clubs and urban radio over the last year, it hasn’t translated into monumental sales or commercial radio play. Tefl on Don has sold a little over 650,000 copies, a solid but less-than-blockbusting number. “Aston Martin Music” and “B.M.F. (Blowin’ Money Fast)” topped out at 50th and 60th, respectively, on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The wave of cocaine-centric rappers who emerged in the mid-2000s—a class that included Ross, Jeezy, Gucci Mane and Clipse—subsided, and a gentler, more whimsical group, led by Drake, Nicki Minaj, Wiz Khalifa, Big Sean and Kid Cudi, flooded in. From a commercial standpoint, have gangsta rappers become dinosaurs? “Most definitely times have changed,” Ross says. “But that increases my value for what I do right now. Because the streets will never change. No matter what the climate in the music industry, muthafuckas still in the struggle, for real, that’s tapped into that. If everybody in the mainstream ain’t catch on, they’ll catch the next one.”

Members of Ross’s crew—his manager, his DJ, his videographers, his security—call him “The Bawse,” or simply “Bawse.” It is a title taken literally. After the Chicago concert, some of these young men lounge in the front of his tour bus, flipping between a preseason NFL game and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. Word is sent from the back that The Bawse has a hankering for Popeyes. Again. There is some grumbling, but everyone respects the hierarchy. “Let’s not be selfish; it’s for The Bawse,” says DJ Sam Sneak, a skinny dude with Foamposites, a Fendi belt and two vicious scars raking down his left cheek. “Make it happen.” Soon the bus is freighted with enough deep-fried poultry to feed a small battalion.

Ross’s sphere of influence has grown to include the Maybach Music Group stable of artists—a collective that, like Young Money or G.O.O.D. Music, has little loyalty to any specifi c philosophy, sound or geographical region. Wale is from D.C.’s street-wear and go-go scene. Meek Mill is a classic blood-and-guts Philly spitter. Pill is an Atlanta rapper who merges social commentary with street narratives. Stalley is an everyman from Ohio. “We have different styles and come from diff erent parts of the U.S., but we tell the same story,” Stalley says. “We were self-made artists who did what we had to do to get our music heard.” He believes Ross is headed for historical heights. “He’s on his way to being Kanye, Jay-Z status,” he says. “To be involved with that is a beautiful thing.” Ross describes “spirit” and “energy” as the character attributes he values most in members of his camp. “To me, it don’t matter where you from,” he says. “I come from a time and place when Miami wasn’t the most poppin’. Everybody wasn’t as eager to open they door, give you a hand. For me to be in this position, I want to make sure I do the opposite that a lot of these niggas did.”

According to Forbes’s list of hip-hop’s top earners, Ross made $6 million over the past year. This pales in comparison to Jay-Z ($37 million) or Diddy ($35 million), but it clearly allows for a comfortable lifestyle. Ross says he smokes an ounce of weed daily. He is on his fifth Rolls-Royce and recently bought a yacht. The dressing room on his bus is strewn with luxury items from Louis Vuitton and Gucci. A cache of jewelry—two Jesus pieces, a diamond-covered Audemars Piguet watch, a pinky ring, colored beads—is laid out on the bedspread next to him. “I’m stacking my money, but there is a side of me that love to fuck up money,” Ross says of his lavish spending. “I could spend $100,000 in one day, just ballin’. If I’m fuckin’ with a chick, I want this chick to know all them niggas is losers compared to me, baby. You gonna eat good with me. I’m gonna put you up on these $10,000 Birkin bags.”

This is not enough. “I want to do that,” Ross says, pointing up at the TV screen. It’s a scene from Blow, a film about a cocaine kingpin, where Johnny Depp is rolling on the fl oor in heaps of dollar bills. “Wait ’til we buy a piece of the Miami Dolphins,” Ross says. “Sitting in the box with the majority owners, smoking cigars. They’ll say, ‘He’s smart.’ ” He snorts. “You just slow.” Beneath the TV are DVD cases for Pretty Woman and Exit Through the Gift Shop, a movie about a street-art documentarian who fools the public into thinking he himself is the authentic article. There are a dwindling number of critics still grumbling that Ross has pulled off a similar caper, but everyone else just wants that “Hunngh!”

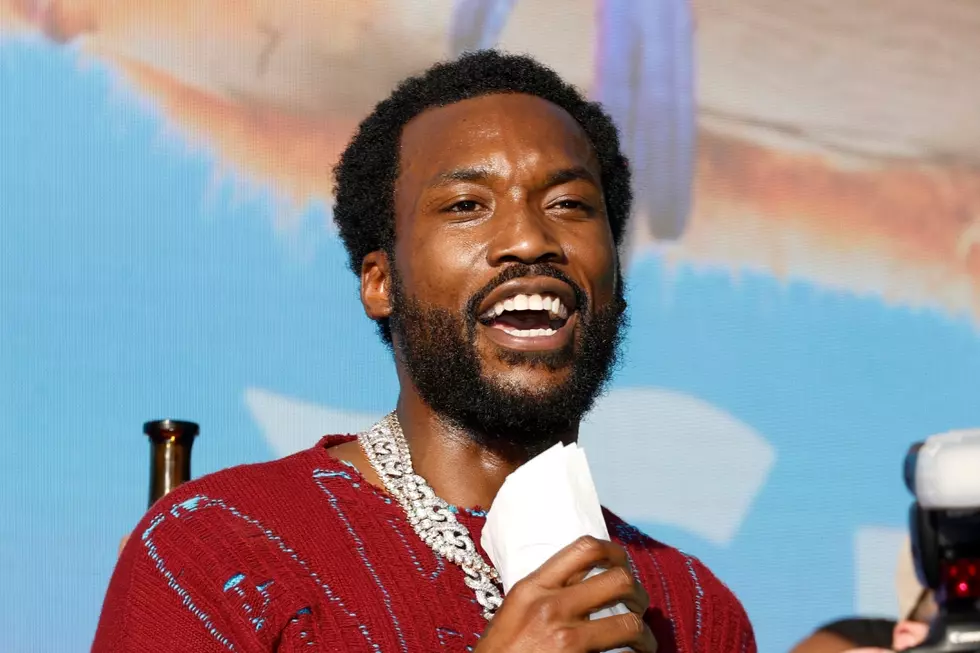

Hailing from three different cities, Wale, Meek Mill, and Pill don't get together so often. But that doesn't stop the leading lights of Maybach Music Group from inspiring one another.

Interview: Jayson Rodriguez

Images: Travis Shinn

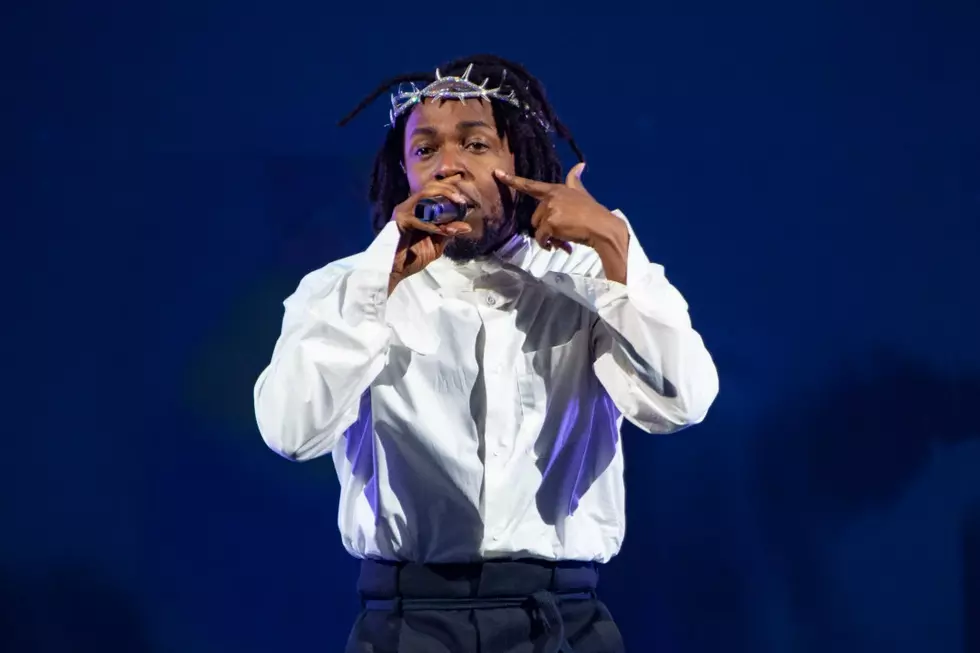

RICK ROSS'S AMBITIONS EXTEND BEYOND REGIONAL BOUNDARIES. WHEN HE WAS assembling the acts for Maybach Music Group, his Warner Music Group subsidiary, he cast his net wide, scouting talent in various cities, doing his research, looking for signs of stardom, before finding the three young MCs who have helped make the label’s first official release, Self Made, Vol. 1, into a No. 1 hit on Billboard’s rap albums chart. The three are Wale, from Washington, D.C.; Pill, out of Atlanta; and Meek Mill, from Philadelphia, whose blistering “Ima Boss” is nipping at DJ Khaled’s “I’m on One” for hip-hop’s banger-of-the-summer status.

They all had acumen, strong local followings and success on the mixtape circuit or with viral videos. And they had all been on the cover of XXL, chosen as up-and-comers for our annual Freshmen issue: Wale in 2009, Pill in 2010, Meek this year. Wale released his first album, Attention Deficit, on Interscope Records in 2009. But it fl opped, and he looks at MMG as a shot at redemption. Pill and Meek are working on their own solo albums. And touring and traveling for promo spots keeps them all hustling. Despite their hectic schedules, there’s a relaxedness when they are together that speaks to a strong kinship. The crew has coalesced and, with the support of the label’s other acts, made MMG a force to be reckoned with. The three sat down recently for a roundtable discussion about where they’re at and where they’re going.

XXL: So what’s the identity of Maybach as a crew? Bad Boy was about the Champagne life, Roc-A-Fella Records was the hustlers, No Limit Records was Dirty South. You guys are...?

PILL: It’s, like, a coalition almost.

MEEK: It’s, like, all around the board. We come from under that shit, so it’s, like, everything all in one now. Whenever I do interviews, I always say my style is like a Beans mixed with a Cassidy mixed with a Young Chris—

WALE: Mixed with a nigga from the South, too.

MEEK: Yeah, them niggas, too.

Is that the strength of the crew, having different elements based on the different regions you all represent?

MEEK: We barely see each other, man. We barely even talk. We gonna keep it all the way real. Do we see each other?

PILL: We usually be on the road.

MEEK: I see Pill in the basement of a party in the A. But we do what we do, getting to the money.

PILL: Exactly. But I think it’s a plus that everybody got their own fan base, they got their own thing rocking in their own city, and they got their own representation of what they stand for. So when everyone comes together, that’s all the fan bases combined. It’s amazing what different cities combined—Miami, Philly, D.C., and New York, with Torch and Triple C’s—it’s a blessing to be able to rock with a bunch of different guys that are passionate about the craft and that know where they going and actually can foresee the future, when it comes to their music. I think that gives us a stronghold and a bit of longevity. And kind of an advantage also.

How would you describe each other’s role in the crew? Who’s Pill?

MEEK: Pill, to me, he’s the deep nigga, the OG nigga, the trap nigga. You know, if you gonna go hang on the block, come to Atlanta, I expect Pill to take me around, get me some nice hood bitches and do what we do.

WALE: To me, Pill is that cousin you got from the South that’s just country as shit. You gonna feel like you live in Atlanta if you hang with him for 30 minutes. He knows what bitches got pregnant or who got shot. He’s, like, the street poet.

What about Meek?

WALE: Me and Meek, we got a personal relationship. A lot of shit happened before we both got signed. He was quoting shit from my mixtape, and I was tweeting his YouTube shit. And Philly and D.C. are so close; it’s almost like I see myself two years ago, when I see him. Everything is so new to him. He’ll get his checks in them brown bags, and I’ll be like, “This nigga right here...”

[Laughs] And all my niggas back home got a relationship with Meek and his crew. That whole Dreamchasers shit naturally happened, without us even being around.

PILL: He’s the young gunner, grinder, spit fire rhymes, hood nigga—he completes the puzzle. You got a nigga who is really going for what he knows right now. If you listen to his music, he’s been in and out of jail, battle rapper, he’s hungry. He displays that real grimy hip-hop shit. Even back then, I heard his shit from a girl from Philly. She had his tape in her car, and I stole it. [Laughs]

MEEK: The first time I heard about Pill, I was in Atlanta, in the studio with T.I. I asked him who the hottest young nigga was. And you know how T.I. is: “I don’t listen to none of these young

bucks.” Not coming at anybody, you know? Then he was like, “But I fuck with that boy Pill’s shit.” That was the fi rst time, and after that I was on YouTube checking his shit out. And Wale?

MEEK: The fly nigga. D.C. nigga. I told him, he’s the nigga, you’ll be joking with him, and then three, four minutes later, this nigga is going through it. What the fuck happened that fast? When you see him sitting there, he’s going through something.

PILL: [Laughs] He’s gonna be the one that put you up on style. He’s always ahead of the curve with the sneaker culture. And another thing, with the music, there’s more emotions. Bitches love this nigga. We almost had to be his security in Las Vegas. Girls screaming, “Can we get a picture?”

MEEK: He’s a substance spitter. Shit that means shit to them ladies. When I do my chick record, he’s gonna write the hook, and he gonna help me write my bars. I’m bad with that. I never had a girlfriend, so I can’t speak to the girls that well.

PILL: That’s wild.

WALE: [Laughs] Meek never had no girlfriend. I don’t know, when it comes to Meek, there’s something about him. I just feel like we were family in anotherlifetime. It puts me in a better mood when he comes in theroom. Every time, whether we are [at a club] or in the studio, he just comes in, “What’s up?” and daps everyone up.

What’s something that one of the other guys in MMG may have achieved—Pill had a big viral video, “Trap Goin’ Ham,” Meek has a street banger with “Ima Boss”—that makes you think, I want that in my career?

MEEK: Wale got shit with Lady Gaga, the VMA look.

PILL: That look right there.

WALE: I peaked really early.

PILL: Get out of here.

MEEK: I was in the hood, like, How the fuck did this nigga get shit with Lady Gaga?

What’s the lyrical competition like between y’all?

MEEK: Who gonna be the fi rst one to cop that muthafuckin’ Maybach or that Phantom, that’s our competition. We all can rap good. I get killed by these niggas sometimes on raps and shit. We don’t compete.

PILL: You bust. You come with your best shit.

WALE: We like a football team. A nigga be a quarterback on a song, a nigga might be the receiver or the running back, but we on the same team. We might go song for song against other people or artists. It’s all love. I don’t think any of us have beef, but when we put out a song—

MEEK: We out to murder you.

So you’re measuring yourself against other crews?

PILL: Everybody ain’t as solid as us. Not to say any names, but niggas ain’t as solid as Maybach Music. Us three alone, not to mention Rozay—add all that in the pot. Gunplay murders shit, Torch, even our R&B side, Teedra Moses and Masspike Miles!

MEEK: We all doing what we gotta do: making money. Niggas just don’t make up reasons to fall out with nobody or shit like that. ’Cause nine times out of 10, you doing you. Every time we run across each other, it’s about something good, not negative shit.

WALE: And, to me, when I hear “Ima Boss” in the club, that’s my song then, too. When he hear “That Way,” that’s his. When I hear “Pacman”—nigga, I thought I was Pill in Atlanta! We did a show out there. I couldn’t fight it. I almost bumped this nigga out the way to perform the song!

What were you each missing individually that joining MMG resolved?

PILL: Me, personally, being able to get a mainstream look. Like, I never got 106 & Park. Although I had MTV and magazines, I never had 106 & Park.

WALE: That’s hood rich.

PILL: I was in The New York Times and Creative Loafing, and it still wasn’t, like, 106. That was, like, the stamp. And to be a part of a project that was in stores, that felt great. That gave me a boost, because I didn’t know when I would be able to get something to retail. That was the one thing I was missing: Could I sell some records? I know I can drop these mixtapes, and I’m working on my project. But there’s always that question in the back of your mind: Can I actually sell? I know my shit is over a million downloads. And I’m like, Damn, I wish that amount of people would actually support. But there’s been projects where I’m on just one song and that did well. I want to know how it would do with me on a bunch of shit. A project with all of us combined [Self Made, Vol. 1], we had a No. 1 album. I never been on a No. 1 album before. I never imagined I could be on a No. 1 album. I hoped and I wished and I prayed that one day I could. But we about to have some plaques in a minute.

Meek, a lot of talented Philly rappers make noise but never break out, but now you’re getting the look.

MEEK: Ross gave me the opportunity. You know how when you’re underground, you say, “I know if people in the world hear me, they gonna fuck with my shit.” And Ross gave me a chance to take it to the next level, and put me in that space. And people are actually fuckin’ with it. Ross put me in the space where I can get the listeners I need. The light he got us in, if you fumble this, you dropped the rock.

Wale, you put out an album before, in 2009, on Interscope Records. You’re a part of Warner Music Group. Is it any different for you?

WALE: I try to share with these niggas all the time. Like I told J. Cole—that’s a great friend of mine—I don’t want you to go through what I went through. If I smell something that don’t seem

right, I’m gonna tell you. Like, “My nigga, this is what it is, and this is what’s about to happen.” I don’t give a fuck. I want Meek to do a gazillion times more than what I did my first album. I don’t want him to go through that shit. I don’t want Pill to go through that shit. Rozay don’t want them to go through that shit. Do you know Rozay’s story, for real? He was signed here, here, there, there and couldn’t get it right. It’s almost identical to me. I was fortunate to be so young coming in. I got my first record deal when I was 22. I don’t want them to go through that. And furthermore, Pucci [Gucci Pucci, Ross’s manager and the general manager of MMG] and them know the game so well, they tell us. And I love that about our crew.

There’s an added dimension to your camaraderie, since you three are all former XXL Freshman picks. Do you talk about that?

WALE: I actually thought about it today, for real. I kind of thought about it, because we here doing this roundtable.

MEEK: Wale always would tell me, “Out of that cover, you know there’s only gonna be two, three people that make it.”

WALE: It’s true! That 28K first week, I had to crawl back. I almost didn’t make it. I’m fi ghting. And that’s what I see with these niggas every day.

MEEK: I told them at the [Freshmen] interview, I said, “We all cool, but I’m about to murder you all.”

WALE: And they probably thought you were crazy. But that’s passion. Not to say everyone isn’t grinding. But it’s like natural selection. That comes from hustle. It’s not even how good your music is sometimes. There’s a lot of niggas that, if they had the opportunity, they might be in this conversation. A lot of it has to do with timing. I say this in every interview: Meek is someone that got a shot and fuckin’ took that bitch to the moon.

PILL: We all trying to do that.

More From XXL