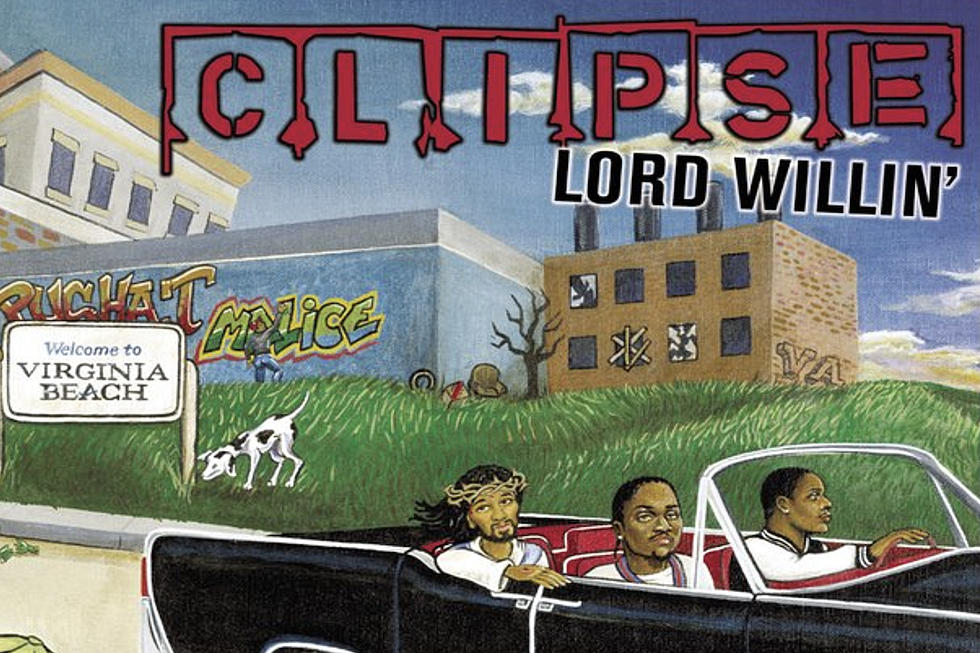

Clipse, “Way Of Life” (Originally Published August 2002)

They’re two hustlers, baby! And they want you to know, it ain’t where they been but where they’re about to go. Pharrell’s prized pupils, CLIPSE are the leaders of the new school.

Written By: Noah Callahan-Bever

Though Malice, the older of the two Clipse brothers, may laugh at the suggestion, it’s clearly true. If one were to reduce the content of the duo’s surprisingly mature and sonically sophisticated new album, Lord Willin’, to one essential sentence, it most surely would be: “I lived off cocaine, way before I lived off rap.”

“Ahh, the drug theme,” he says, seated in the mirrored den of his parents modest Virginia Beachhome. “I think it’s so prevalent because the album came together at a time in our lives when that’s exactly what was going on.” Like any good paranoid hustlers, Gene “Malice” Thornton and Terrence “Pusha T” Thornton dance self-consciously around the details of their sordid former profession. But their lawyer-like knowledge of the Virginia Commonwealth penal code, combined with the cold-blooded and too-specific-to-be-fictional words of Lord Willin’, reveal their gangsta.

“You can kinda tell it does wear on my conscience,” Malice admits hesitantly, before passing the onus to his sibling. “But Pusha will tell you, ‘You get to be ignorant on the first album…’” Pusha T concurs, his broad smile and soft features making him look like a cartoon of his lithe, chiseled brother. “We’ll probably try to save the world next album,” he says, hinting at a Criminal Minded toBy All Means Necessary-type turnaround between releases. (A strong KRS-One influence can be heard in Malice’s rigid flow.) “But this one had to come out the way it did, man.”

* * *

Entering existence in 1973 in the Gunhill Road section of the Bronx, Gene Jr. was the first child born to Gene and Mildred Thornton (his mother had a six-year-old son from a previous relationship, Charles). A decidedly non-malicious child, Gene was nonetheless mesmerized when his older half-brother introduced him to hip-hop through freestyling ciphers and breaking sessions on the family’s block.

The Thornton four became five in ’78 when Terrence was born, and one year later, as their neighborhood declined, the clan relocated to Mildred’s childhood home of Virginia Beach. “I remember thinking how slow people talked,” says Malice. “And seeing someone walking on the street with no shoes on, and thinking it was the strangest thing.”

A quiet, working-class community tucked behind the beach’s booming strip, the new locale seemed like an escape at first. But, as in the case with so many American suburbs, the emerald foliage and freestanding houses fostered their own version of vice. It was there, in Virginia Beach—the seemingly serene, middle-class land of lovers—that the Thornton brothers learned the game that would come to change their lives.

Both parents were hardworking law-abiders. Mildred spent days at the post office, Gene Sr. at a pharmaceutical lab (how’s that for irony?). But it was their grandmother’s ability to turn five into eight that really impressed the boys.

“I didn’t know where her income came from,” says Malice of the women he compares to Madame Queen (from the 1997 gangster flick, Hoodlum) on Lord Willin’s “Out of Line.” “I just knew she had a lot of money. I can remember as a child playing around with my cousins, we would always come across something like, ‘What’s that?’ Finding scales and stuff.”

Thus, the taboo surrounding dope was removed early on. In the mid-‘80s an adolescent Gene took up a trade he refers to as a “family tradition” when he began pushing crack on neighborhood street corners. “I got two cousins where we used to get the money at,” he explains matter-of-factly. “They ran it, so it was easy.”

While Gene lost interest in school, Terrence excelled with little effort and, when he was nine, actually staged an intervention for his 14-year-old brother. “I started to notice his new gear,” says the once-concerned Pusha. “I started to get worried, so I pulled him to the side to tell him he was messing up.”

In the late ‘80s, though, the money to be made off crack made for a hard argument to beat. Eventually, Terrence followed his brother’s footsteps and opened his own operation.

In 1992, Gene, fresh out of high school, was realizing the danger of his continued hustling. He began cutting back from the time on the block and started making forays into the VA hip-hop scene under the alias Malice. But then, after impregnating his girlfriend, the fresh young MC was forced to put his dream on hold, in need of steady, taxable income, Malice enlisted in the Army for two years and 23 weeks, the shortest tour they offered.

Luckily, before he left for Fort Bragg, mutual friends introduced Malice to Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo—fellow Virginia Beach music makers who had the good fortune of working under local legend Teddy Riley. “We just clicked,” Malice remembers of meeting the future Neptunes. “We’d just make songs together at Chad’s house, no matter how much his parents would scream on us.”

* * *

By the time Malice earned his military discharge in ’94, Pharrell had already scored his first platinum plaque for penning Teddy Riley’s “Rump Shaker” verse. His friend’s accomplishments was proof to Malice that a career in music could be a reality. And he got some help from those around him.

“My girl was like, ‘Well, I don’t work. I’ll work. You stay at home and do your music,’” he says, still awed by her understanding. “And that’s exactly what the fuck I did.”

Malice went to work with The Neptunes on making a demo. At the same time, he was dabbling in the streets to make ends meet—running with his little brother.

Though never drawn to rap like Gene, the book-smart but directionless Terrence enjoyed hanging around his brother’s recording sessions. One day, on a whim, Pharrell insisted that the 16-year-old hop on a posse cut. From the moment his verse hit the reel, The Neptune boss saw the potential in the sibling rhymerly and Malice’s solo act became a duo. Terrence took the MC name Terror.

Originally calling himself the Full Eclipse Crew, which they clipped in light of the Terror Squad-affiliated Full of Clips Crew, the brothers cut a demo over some “dreamy” Native Tounge-ish Neptunes tracks. Reared on the old school, Malice brought a stiff cadence and broad vocabulary to the songs, while the younger Terror contributed to a looser, unconventional flow.

Malice, Terror and Pharrell spent the next four years trekking from Virginia to New York and back, meeting with every label from Quest to Tommy Boy to Priority. All to no avail.

Finally, in ’98, The Neptunes broke though as producers of Noreaga’s “Superthug” and Ma$e’s “Lookin’ At Me” and used their newfound cache to start up a production deal with Elektra. Clipse were their first signing. The four set to work at home, and by year’s end had an album completed,Exclusive Audio Footage.

At their producers’ insistence, during recording, Malice and Terror kept their noses (and those of their customers) clean. “That album was nothing more than friends together doing something they love,” says Pusha of the group’s initial effort. “No outside interference, no arguing. It was all happy times.”

Offbeat and interesting, with song titles like “Breakfast in Cairo,” Exclusive boasted some strong beat work (the first track on the LP would become Jadakiss’ “Knock Yourself Out” in 2001). But truth be told the four weren’t yet ready for prime time. The ‘Tunes relied too heavily on the “Superthug” guitar sound, and both MCs strained their voices, with less-than-convincing results.

They shot and serviced a video for a single, “The Funeral,” in the fall of ’99. Radio reaction was weak, however, and Elektra pushed the release back to 2000. Sensing years mired in contract hell, Neptunes manager Rob Walker was swift in extricating them from the label.

“I’m gonna tell you who was disappointed the most,” says Pusha. “That was Pharrell. He was like real hyped about working with [established artists] but he’s always been like, ‘Yo, we gotta show them how we do it.’”

After their first at-bat strikeout, the brothers went back to the block. They had to make money, even while Pharrell kept talking that music shit. Terrence would abandon the name Terror for the more appropriate Pusha T (The “T” now standing for “Ton”).

Despite the failed business venture, and some lost luster after N.O.R.E.’s “Oh No” bricked, Pharrell and Chad stayed hard at work as boardsmen-for-hire. In the fall of 2000, on the shoulders of two giant crossover smashes—Jay-Z’s “I Just Wanna Love You (Give It To Me)” and Mystikal’s “Shake Ya Ass”—The Neptunes emerged as pop music’s hottest hit makers. The next year, in between assignments from the likes of Britney Spears and ‘NSync, Pharrell and Chad went into business with Arista—forming their own label, Star Trak, with Rob Walker as CEO. Of course, again, Clipse were the first to join The Neptunes’ roster.

With The Neptunes splitting time between Babyface’s next project and Lord Willin’, the foursome went into production in LA. They knocked out the first five tracks in as many days, but, as they’d so painfully learned before, all the industry juice in the world can’t break a new artist. You need a joint, and a dope one at that.

“I’d be like, You got some aight joints,” says Pusha, with a sly smile, describing how he goaded his longtime friends into making their magic. “But you have not made no muthafuckin’ crucial shit. Look, I think you’ve been going to the movies too much. You get Hollywood? You rich?” He laughs out loud. “Pharrell started yelling, screaming. Called Chad, asked him, ‘Do you hear this shit?! Do you hear this shit?!’ He said that a thousand times, and then kicked everybody out of the room.”

Hours later, Pusha’s phone rang. It was Pharrell. “He was like, ‘I got some heat for you,’” says Pusha. “But if you don’t get back here in exactly seven minutes, I’m giving it away.’”

Needless to say, he and Malice showed up in less than seven minutes—but not everybody was ready for the bare-bones rhythm science that Pharrell had concocted. “I was like, ‘Pharrell, something’s missing…’” Malice admits. “And I’m ashamed of this…I don’t even wanna say this…I think I’ve been lying in every other interview, but I’m gonna tell the truth: I didn’t get ‘Grindin’,’ man!”

It’s understandable. The shit is challenging. In fact, Clipse approached the abrasive, futuristic-yet-old-school beat three different ways before finding the perfect fit—dedicating it in the end to the focal point of their adult lives: the grind.

* * *

As their undeniable hit blasts from radio of Malice’s gray Benz truck, the duo reveal their insecurities about the long-time-in-coming debut. For his part, Malice is concerned about the album’s late August release date. Pusha admits to being “addicted” to SoundScan’s sales figures (he can quote the stats on almost any current rap release) and prays that the group break 100,000 in their first week.

“We’ve thought that it was all good before,” says Malice. “And then watched it turn to shit. So we know that nothing is guaranteed.”

“That’s why we stay humble,” adds Pusha. “All that we want from this rap game is the ability to provide our families, to scoop our peoples off the street and make this music that we love.”

Indeed, the grind is about family, never been about fame.

More From XXL