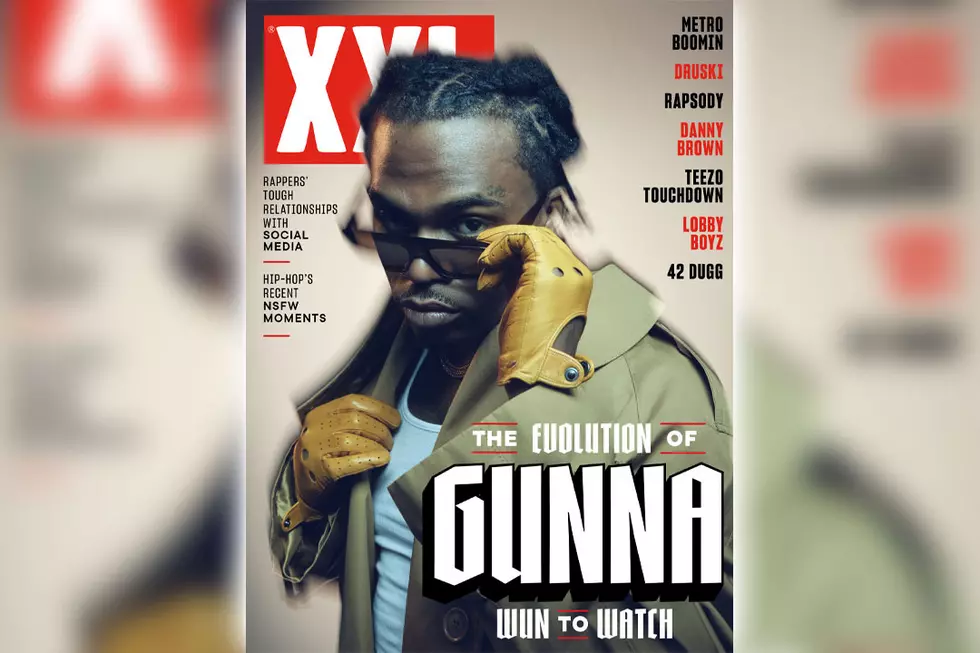

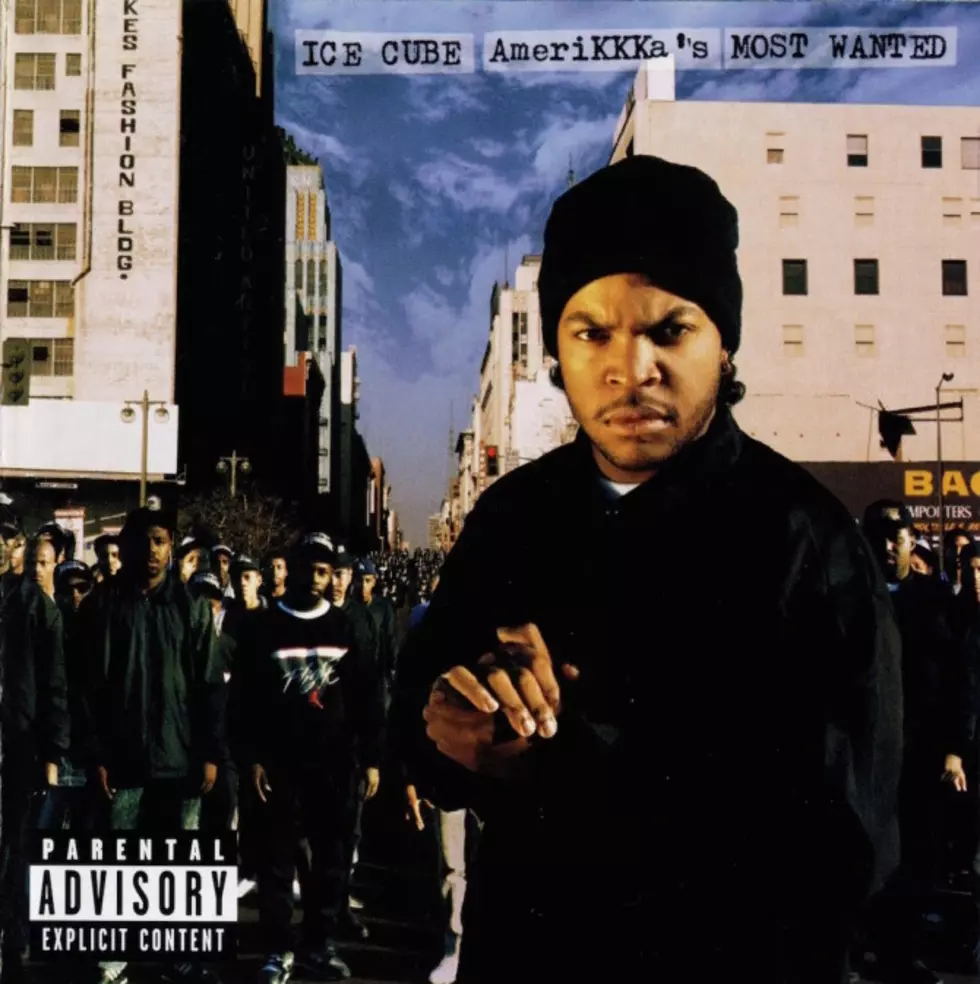

Street Knowledge: Ice Cube on 25 Years of ‘AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted’

Political hypocrisy. A violent police force. Inner city angst. Tales from the dark side. Sometimes it's hard to tell whether society has progressed at all over the past few decades. But those are themes that run the duration of Ice Cube's iconic solo debut album, AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted, which turns 25 years old tomorrow (May 16, 2015). At the time it was a sharp political and social message—just as his writing in N.W.A was, just as Public Enemy was doing on the other side of the country—and its impact isn't lessened by the intervening quarter century. If anything, it makes Ice Cube's contribution that much more significant.

Twenty-five years ago, Cube was still just 20 years old and coming off an acrimonious and bitter split from his N.W.A brothers over a royalty dispute. Label politics and general bad blood meant he had to look elsewhere to find the backing and support to make it on his own. On a trip to the East Coast in search of 3rd Bass producer Sam Sever, Cube ran into Chuck D in the Def Jam offices, who brought him over to see Public Enemy's production crew the Bomb Squad. With Cube's trusted sidekick Sir Jinx in tow, they would form the backbone of an East Coast/West Coast connection that would produce Cube's iconic debut. From the ashes of controversy rose AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted.

All this time later, Ice Cube's first solo album stands as a time capsule of West Coast swagger over East Coast sampling, the unification of two very different philosophies for the higher goal of durable music. It's stuffed end-to-end with harsh realities and eye-opening stories, shedding light on what was really going on under the hood of America's biggest cities. "What I was trying to get across was a true definition of street knowledge," Cube says now, "Where you can bump my record but you can learn from it, too."

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted, XXL spoke to Ice Cube about the making of the album, rappers' responsibilities to speak out on social and political issues and how, one way or the other, the world always comes back around. —Dan Rys

XXL: When AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted first came out, you were in the middle of a bitter feud with N.W.A. Now, 25 years later, you're celebrating this anniversary while you're in the middle of working on the N.W.A biopic Straight Outta Compton. Is that strange for you?

Ice Cube: Yeah, it is. It's very surreal, 'cause when I was 16 years old I wrote "Boyz N The Hood." Ended up years later doing the movie Boyz N The Hood. From the record "Boyz N The Hood" we made the album Straight Outta Compton. That was the start of it. And my first movie was Boyz N The Hood, so 25 years later here we go doin' the Straight Outta Compton movie. I believe everything go full circle and here we are. And what's even crazier is, like Boyz N The Hood was my first movie, Straight Outta Compton is gonna be my son's first movie. It's crazy.

A lot of the themes you spoke on 25 years ago on the album—social, political, police issues, racism—are just as fresh and relevant today. How do you feel about that?

It just lets me know what I've always thought; the powers that be don't want it to change. They want the status quo. Nobody wants to give up power. People will give up money but nobody wants to give up power. I just think that's really what it is. And America, the system now that we're under and that we use, is a pyramid system of capitalism. You've got the bottom and you've got the top. Somebody has to be relegated to the bottom of the pyramid, it just happened to be the minorities in this country who have been relegated to the bottom. And you have to fight your way to climb up that pyramid. And that's really, to me, the issue and why it can't change.

Do you think there's any way that can change at all or is that the status quo that will just keep continuing?

Well, I think that if people keeping fighting the good fight then things will change. If people sit back and be complacent and not really care then it'll stay the same. Or not care until there's an incident, a killing or a shooting. You gotta care when when something's not going on.

And that's the hardest time to get people mobilized, when there's not something going on.

Yeah, because people like to use their emotion and their adrenaline to help get things done. But sometimes the best work gets done in the quietest room.

Do you feel like enough rappers today are speaking up on the issues that you were rapping about 25 years ago?

Yep. Yep. Because artists should have the freedom to do what they feel. So if they don't feel like talking about it, they shouldn't. They shouldn't pretend to be something they're not. They shouldn't take on issues that they're really not equipped or concerned to take on. Just to satisfy who? I don't care how many records you put out about what's happening in the world today, they still gonna play the booty records in the club. The radio station who wants to be so positive, all they play is booty records, they don't play nothin' positive. They want us to stop rapping about it, but they won't even play it if we did. It's crazy. It's hypocrisy. Rappers shouldn't deal with hypocrisy. Rappers should just be as real as you feel. That's what it's all about.

Back when you were recording AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted, the East Coast and West Coast were very different, stylistically. One of the biggest surprises on this album was that it was almost entirely produced by Public Enemy's production team The Bomb Squad. Why was it important for you to cross that divide?

At the time they were my favorite producers, because Public Enemy records were the most dynamic records in hip-hop. They were like what we were kinda striving in a lot of ways to aspire to as locals in L.A. to figure out your flavor. P.E. made us put the street stuff we were going through in perspective. So that's how I came up with the concept of street knowledge. You got the street stuff, you can always do that, that's always there. But can you put the knowledge with it? And can you make street people listen to it? And can you make politicians understand what's going on in the streets by listening to it and think? That's kind of how we saw P.E. and why they were so big and influential.

Do you have any favorite memories of being in the studio with them? Anything that sticks out to you about making that album?

Just the people that would fall through and say what's up while we was doin' the record. Everybody from X-Clan, Busta Rhymes, Flav would come through every now and then to hang out. When we was in Long Island at they spot at—I think it was 17 Franklin Avenue, they had a spot there—and EPMD, K-Solo, Redman, all them would fall through, scoop me up, take me to the hood, hang out with them, man. It was cool like that, you know.

And then we was working on the album and I had my guy Sir Jinx with me; Sir Jinx is the reason why the record still feel like a West Coast record even though it was produced by the Bomb Squad. He was a producer on that album, too; a lot of those tracks are his, too. "Once Upon A Time In The Projects," "The Bomb," I think "What They Hittin' Foe?," "It's A Man's World," those are his tracks. Jinx put all of those skits together with me. I think the combination of this young, West Coast producer kinda helping them maintain the Ice Cube sound but working with some of the best rhythm samplers and dynamic samplers out there, which was the Bomb Squad... Nothing sounded like their music at the height of sampling. It was incredible. Eric Sadler [of the Bomb Squad] is a master at rhythm.

Were there any lessons you learned from making that album that you've held on to over the past 25 years?

Oh, yeah, man. Chuck D really taught me a lot about sequencing a record, how to put an album together. Because before, I would go into the studio with Dre, I would have a few ideas, but Dre would really mix that shit up, you know what I mean? Throw our ideas on top of what he doin' and voila. But with the Bomb Squad it was like, our first lesson was, when we went to their studio in Long Island they had a shelf full of records, it was records everywhere. They just walked out of there with two old-school milk crates. "Here's a turntable, listen to these records, find your album." I was like, "What?" [Laughs] "Listen to these records and find your album. When you fill up these two crates with the shit you wanna do then we'll start working." It took us 10 days to fill up the crates. So once we filled them up, then we went to Greene Street [Studios] and Eric Sadler started saying, "Okay, what y'all want to do with this?" We had to write down everything we wanted to use, where it appeared in the record and the sample information. It was homework. Homework.

It's that business side of things that people never think about.

Yeah. Shit can get tedious, man. You know, if you're not a pro or trying to be a pro, you're bored and you fall off. Like, "I'm gonna go do somethin' else," and then your record is trash.

How do you feel like the album has held up a quarter century later?

I love it, it's dope. It's one of my favorite albums that I've done. I think it's a real important record because it fused the East Coast and West Coast for a minute and showed that we were one hip-hop nation for a brief moment. It showed people what could be possible, you know what I mean? People could work with anybody from anywhere and make a good record.

Do any songs on there particularly hold up well for you?

"AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted," "Nigga You Love To Hate," "Once Upon A Time In The Projects," "Endangered Species," "Gangsta's Fairytale." The record is solid. It's a good record. Damn good record.

Was there a particular point you were trying to get across with the album? And all these years later do you feel like you were successful with it?

What I was trying to get across was a true definition of street knowledge, where you can bump my record but you can learn from it, too. And yeah. I know it's made an impact, 'cause I've had fans who've come up [and said], "Yo, that record changed my life," or, "That record made me start thinking in a different way." All these good things that good art inspires in people. So if it was trash, it wouldn't touch nobody, or touch them in the wrong way. But the people that thanked me for... Like, when somebody said, "Yo, I grew up listening to you, I grew up on that record," that's powerful. It means the person learned some lessons from your record, like I learned from Marvin Gaye and I learned from Curtis Mayfield and Earth, Wind & Fire. It's the same thing.

It must be crazy to know that you're in that category, in a different genre, as guys like that.

I mean, it's where you want to be 25 years later. You want to be an artist's artist. You wanna be in the same breath as a Bob Marley or one of the greats that, not just rocked, but influenced people in a lot of ways. I just feel that I'm blessed to be in that position, and humbled, and also courageous, you know what I'm sayin'? I feel that nothin' I did was a mistake, even if it cost me success in different ways. When you're a political artist, a lot of people don't like that.

You get a lot of backlash.

Yeah, you know. Not public backlash, but behind-the-scenes backlash, corporate, you know what I mean? Some circles. Very little, though. Most people love the shit out of me. [Laughs]

Related: Ice Cube, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted Retrospective [20 Years Later]

Ice Cube Calls N.W.A’s Rise a David vs. Goliath Story

13 Rappers Remember Eazy-E on the 20th Anniversary of His Death

Ice Cube Debuts N.W.A. Biopic Trailer In Australia

Ice Cube Teaches Elmo A New Word On Sesame Street

Ice Cube Is Trying To Convince Dr. Dre To Make New Music For The N.W.A. Biopic

Ice Cube Will Be Played By His Son In N.W.A. Biopic

Ice Cube Gives Details About N.W.A. Movie

The Early Days Of Ice Cube

Ice Cube Wants To Get Back To His Gangsta Rap Roots On New Album

More From XXL