The D.O.C. Is The Secret Weapon Behind N.W.A.

If they wrote a book on the life of D.O.C., you think anyone would read it? They should, f*@kers. Y'all have to wait, though. The secret weapon behind the N.W.A. franchise has a new LP and a few more chapters to live.

Words Gabriel Alvarez

Images Mike Schreiber

The weekend could not have been better for 21-year-old Tracy Curry. Even though he was working on a video shoot in Los Angeles, he was all jokes and laughs. Better known to the world as the highenergy rapper the D.O.C., he held a framed gold record for No One Can Do It Better, his debut album on Ruthless Records. The LP had been released six months earlier and had already sold over 500,000 copies. He took a healthy gulp from his beer and smiled.

This was not the first gold record he had received. Back in his Agora Hills, CA home, the talented Texas transplant had award plaques for Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It and N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton, two other very successful LPs featuring his essential behind-the-scenes contributions.But this felt even better. After years of ghostwriting lyrics for Eazy and producer extraordinaire Dr. Dre, the D.O.C. had finally stepped into the spotlight. He had delivered big-time, and truth be told, he felt like he was only warming up.

The a.m. rap radio station KDAY had continuously spun the D.O.C.’s incredible single “It’s Funky Enough” all summer long. They, like the rest of the nation, had also taken a liking to a smoother-thansmooth track called “The Formula.” That was the song Curry was shooting a video for. It takes place in a smoky laboratory where the diabolical Dr. Dre pieces together the world’s greatest MC. That creation, strapped to an operating table, was none other than the D.O.C.

On the set, surrounded by N.W.A homies, foxy female extras and an exotic mist made by many lit spliffs, Doc, as everybody calls him, waited for his call to jump back in front of the cameras. It was November 1989, two weeks before Thanksgiving, and this up-and-coming rap superstar had plenty to be grateful for. The D.O.C.’s madman howl cut through the thick air of noisy conversations and clanking bottles. No, it didn’t get any better than this.

Tracy Curry grew up in the West Dallas Projects in the late ’60s. By age 20 he’d become an architect of the genre labeled gangsta rap, but his humble beginnings couldn’t have been more different. “Comin’ up as a young guy I was not a hard-rock, thug nigga or street nigga,” says Doc quite openly. It’s a dozen years later, November 2001 to be exact, inside a spacious, wellkept Dallas loft. “I was an introvert really. I spent a lot of time in the crib reading books. Staying out of trouble.”

Because his parents worked long and hard at their blue-collar jobs, Tracy, the youngest of four, spent a lot of time at the homes of relatives and family friends, and regularly attended church, where he excelled in the choir. “When I was young, I had a beautiful singing voice,” he says.

But he was also heavily into rap, inspired by Rakim’s brilliant lyricism. By high school he and a friend had started the Fila Fresh Crew. Their DJ, Doctor Rock, had lived in LA, where he’d been in a group with popular beat-man Dr. Dre. Eventually, Doctor Rock invited his old cohort to Dallas. Andre Young was then making noise with N.W.A on the independent Ruthless Records, owned by street-hustler-turned-music-impresario Eazy-E. In 1987, Dre asked the Texas trio to return to Cali to work with him.

For the D.O.C., this was his big chance. When he moved to the City of Angels, his first shock came when he discovered his neighbors were gang-banging Bloods. “Straight outta Texas, man, I was seein’ and hearin’ things that was blowin’ my mind,” he says. “I had seen the movie Colors, but [now] they was doin’ it for real—right outside!”

Despite the desperation outside his door, the D.O.C. was immediately satisfied working on Fila Fresh cuts for N.W.A and The Posse. One joint in particular, the superb “Tuffest Man Alive,” holds a special place in the D.O.’s heart. “That was the first time me and Dre had ever done something together,” he says. “Just his beats and my words. And it was raw. That song took about 15 minutes. When we did that song, I knew that that was a marriage—that was the shit.”

The D.O.C. split from his FF potnas to go solo, but first there were dues to be paid working on Eazy-E’s album. “I know what a hit record sounds like,” says Doc. “That’s what I brought to the table. An extra set of ears that everybody trusted. And my skills with the pen were pretty goddamn good.” The D.O.C. based his rhymes on gangsta tales he heard from those living the life.

It took a mere six months before Doc found himself on the set of the video for “We Want Eazy,” a song he wrote. The D.O.C. stood to make some good money off his contributions. But he was still a novice to show biz, so he didn’t think much when Eazy traded him a flashy gold chain—the standard rapper accessory—for his publishing rights. “That was dumb decision-making, but I was a kid,” he says. “I knew nothin’ about the business, and to me it was all about the family. Eazy was the figurehead of the family, so I trusted him. Whether it was the right or wrong thing for Eazy to do is not my judgement to make. My train of thinkin’ was, ‘My time is gonna come. And I’m gonna show my ass.’”

No question the D.O.C. helped detonate the explosion that would come next—the classic Straight Outta Compton. Here were fascinating glimpses into a bleak, shocking world. “Me and Dre, we just took that shit and made it Hollywood. Made it where John Q. Public can hear it and understand it, instead of be scared of it.”

People were not scurred, they were enthralled. Many took to Eazy’s character, a lil’ loc with an ill voice. Others clung to Cube and Ren’s bulletproof lyrical skills. And, of course, there were Dre’s megabeats. But what about the D.O.C. (who at least got to rep on the banger “Parental Discretion Is Advized”)? He’s often described as an “honorary member” of N.W.A, yet his input was undeniably integral.

“When we would do these tours,” he says, “I would be in the [hotel] lobby—don’t nobody know who I am—and the kids is rappin’ Eazy’s verses, tellin’ each other how cold Eazy is. I just took all that in.”

Besides, he was finally getting to make his own record. During breaks in touring, Dre and Doc would hit Audio Achievements studios in Torrance, CA. Back out on the road, the rapper would test his songs in front of sold-out crowds during N.W.A’s shows. “Muthafuckas,” he says, “would go apeshit.”

No One Can Do It Better, which eventually sold 1.5 million units, was a blend of hunger, timing, confidence, raw talent and styles upon styles. For the breakout single, Doc dropped four verses in an aggressive Caribbean patois. “Actually, ‘It’s Funky Enough’ was one-take,” reveals Doc. “I was just playin’ around. I did the song in a Jamaican [accent] because the beat sounded Jamaican to me. After that take, Dre was like, ‘I’m not changing shit.’”

The album took off immediately, and when the D.O.C. finally stepped into the spotlight, he did it with a vengeance. “You couldn’t tell me shit. I was the coldest muthafucka to ever rap. And all the bitches wanted to suck my dick. Because I’m hangin’ with N.W.A and then later because I got a 320-lb. giant shadowing me around. Shit, that will give [you] the delusion that you’ll beat everybody ass,” he confesses. That giant was Suge Knight, who became a close friend.

There was a memorable show in Chicago, his first solo performance, in the same concert lineup as Slick Rick, Geto Boys, 2 Live Crew, EPMD and Ice-T. “I’ll never forget it,” states Doc, who followed the night’s opener, the great Slick Rick. “I’ve done a gang of drugs and fucked a gang of hoes and I never felt this feeling ever. “My right hand to the sky,” he swears, “After I got off that stage, muthafuckas [in the audience] started leavin’. After that day, dog, you coulda stuck a fork in me, ’cause I was done.”

Past 3 a.m., the brand-new Honda Prelude screeched around corners and raced through yellow lights in privileged Beverly Hills. The D.O.C. was behind the wheel.

It had been a hell of a weekend. Fresh on his mind were the ladies who had made themselves available at the video shoot. Maybe a little bit too much on the mind. He ran a red light. Like clockwork, police pulled him over. The two White cops made him get out. While one was preparing the ticket, the other spotted a camera in the back seat next to some gold records. When it was discovered that they had a celebrity in their presence the cops had an idea. A picture of them holding the gold records, another of Doc signing his ticket. After some chuckles, the officers said goodnight. Doc got back inside his car, and started flying down the mostly empty 101 Freeway. Fatigued from back-to-back 18-hour work days, and drowsy from weed and alcohol, he stepped on the gas.

When the automobile veered to the right and hit the divider, the D.O.C. didn’t see it happen. He had passed out. The car ricocheted, crashing into a concrete barrier. On impact, Tracy Curry was hurled from the driver’s seat and smashed through the back window. His body bounced off asphalt and lunged off the highway. Most of the injuries were to his head. At the hospital, he underwent more than 20 hours of reconstructive surgery.

Those first few days he slipped in and out of consciousness, making out some familiar faces: His beloved mom, Dre and his girlfriend Mic’hele, Eazy-E and his business mentor Jerry Heller, industry executive Sylvia Rhone, and Suge, who was there throughout his entire stay. Still, Doc doesn’t remember much about the experience. “The funny part about the whole thing is that most of those two days [before the car wreck] I was shootin’ a video where I was gettin’ put together piece by piece. And the very next day the shit would be happening for real.” He pauses. “It’s some deep shit.

“Dre said my head was the size of a basketball,” he continues calmly.

Considering the severity of the wreck, it was nothing less than a miracle that not only did he survive but he suffered no broken bones. The fact that his larynx was dislocated was minor considering he could have died. “It really hadn’t hit me that my career was gone,” says Doc. “Hell, I was very happy to be here.”

His voice had been transformed to a husky growl. Yet, according to doctors, there was hope for recovery. Vocal therapy was recommended. “So I had to go to these places and the shit was humiliating. I know that it was only supposed to be helpful, but it was killing me on the inside.”

He was told by medical experts to quit drinking alcohol and stop smoking. “But shit, those were my only friends to really get away from that pain. I was like, ‘Man, fuck that.’”

A decision had to be made. Would he rap again? He was submerged in selfdoubt. He decided to ask Dre, the person whose opinion he valued the most. “When I asked him, he says, ‘I wouldn’t do it. They say you’re the king right now. I would go out like that.’ So me havin’ as much respect for Dre as I had, when he said that, that was pretty much it.”

But it was not the end of the D.O.C.’s career, because his writing skills were even more valuable now that Cube had left N.W.A. “[Dre] says, ‘We got a good thing goin’. You makin’ money writin’. Stay up here and write these songs and let’s get paid.’ I was like, ‘I’m with it.’”

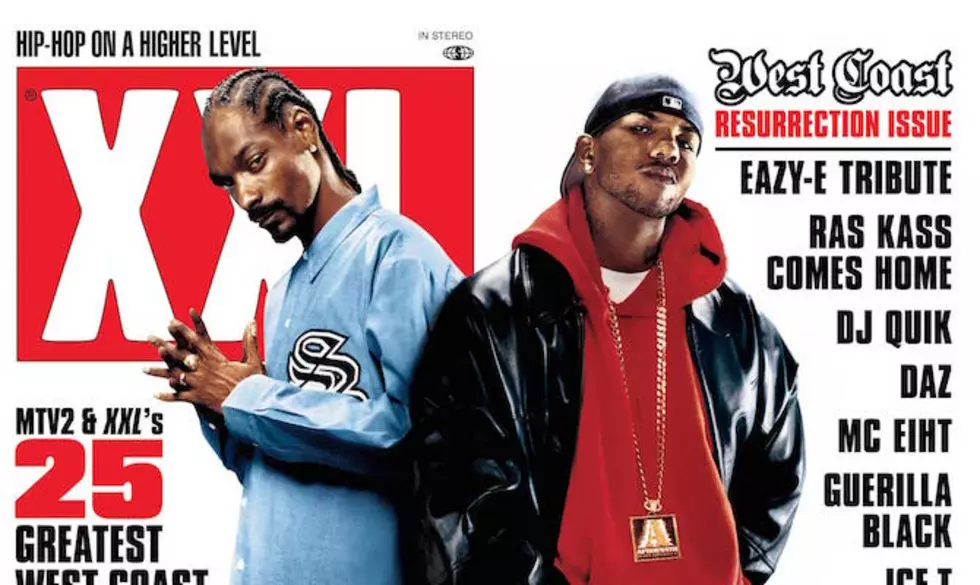

Doc still had some of his best verses ahead of him. But he began having a difficult time coping. He was older and wiser and knew that his work was worth more than what he was getting paid. “Shit used to really bother the fuck out of me,” says Doc. “I gotta sit on the sidelines. I can’t say shit because my voice was even kind of a joke. I just gotta sit and be quiet and take the shit. But in my eyes, when Dre won, when Snoop won, I won—in my mind. Because in the world it wasn’t like that.” He chuckles. “When we go to the ceremonies muthafuckas want me to move outta the way. I’m always just a click out of frame.”

Worse, the D.O.C. didn’t like the person he had become. “I was a total fuck-up,” he says. “I was 2Pac before 2Pac was 2Pac. I was just terrible. Just walk into clubs slappin’ bitches for no reason. Thinkin’ back on it, man, that was not me. I don’t have a problem doin’ the right thing. My mama would have been ashamed of me for actin’ like that, man, and... there’s no excuse. But I was goin’ through that pain.”

Soon, Doc and Dre left an unhappy situation at Ruthless with the notorious help of Suge Knight, started Death Row, and blew up beyond belief. This led to even more pressure as murder and mayhem ensued. But for Doc, a lot of it was blurred. Incredibly, he tempted fate by drinking and driving. He didn’t always show up to the studio, and he was getting arrested. But despite the chaos, the D.O.C. somehow still managed to deliver the goods on one classic after another. With the addition of Snoop Dogg, The Chronic was a massive hit that would be felt for years. And besides writing rhymes, Doc coached Snoop and Dre. There would be fun times, like recording the hilarious “$20 Sack Pyramid” or hanging at Snoop’s apartment with Kurupt, Warren G, Nate Dogg and Daz, who encouraged Doc to rap at their freestyle sessions.

By the time they made Snoop’s Doggystyle, the turmoil was building. “Suge told me one day, ‘Man, I’m finna have it and I’m not finna let nobody stop me.’ What he was sayin’ was, ‘You fuckin’ up, but I’m not fuckin’ up. You fuck up if you want. I’m finna be rich.’ And I understood. And from that day on our relationship was... strained. It wasn’t the same.”

Shortly after that, in early 1994, Doc decided he had had enough of the madness in Los Angeles. He moved to Atlanta and started recording with his homeboy MC Breed and producer Erotic D. “But I wasn’t ready,” says Doc about the poorly received Helter Skelter. “I was still gettin’ fucked up. That album for me, actual work time, was maybe a week.”

He also sued Death Row, to get, as he describes, “my lil’ bread.” In the process, him and Dr. Dre got embroiled in a war of words in magazine interviews. “Dr. Dre is about the closest thing I got to a brother,” says Doc. “Me and Dre, we’ve come almost to fightin’ how brothers do.” The case was settled a few years later. “Dre gave me a call and said he was getting ready to start a new record. He wanted me to come help him out,” says Doc. “As an artist, working with Dre is something I would never say no to. At that time, I wanted to get back with my nigga and make some music. So we sat down and had a glass of wine and buried all of our hatchets. And we talked about the future.”

In 1997 Doc heard a demo by a group called Genocide. He was quite impressed with the startling skills of Forth Worth, Texas spitters 6Two and El Dorado. He was eager to meet and work with these fresh new cats. “I told [Dre] about 6Two, let him hear some of his shit,” says Doc, who signed both MCs to his new imprint Silverback Records. “He said, ‘You’re right, he’s the future.’

“I’m gonna do what I can to blow Dallas-Fort Worth the fuck up. And help these young guys,” Doc states.

Backed by well-crafted live instrumentation and a slew of scorchin’ Southern syllables, the two-years-in-the-making Deuce is a sturdy and dirty collection of heat usually found in recently discharged pistols or horny girls’ underwear. The Silverback roster rhymes solidly throughout with the D.O.C. stopping by here and there to deliver an impassioned verse, a sinister hook or just some good ol’ shit-talking.

Shit gets thrilling on “Tha Shit,” a N.W.A reunion of sorts featuring MC Ren and Ice Cube as well as Xzibit. Says Doc, “We didn’t skip a beat. It was exactly as if a session from 19-fuckin’-88 was just yesterday.” Dr. Dre lends his presence on the chorus of the mackalicious “Gorilla Pimpin’.” The standout “Ghetto Blues” finds the D.O.C. baring his soul. His verse is actually from a prayer written early last year. “I realize now the mistakes that I made back then, spiritually,” he says. “And I wanted to make sure that God knew I knew.”

And as far as his young guns are concerned, Doc vows, “I’m not gonna allow them to go through none of the stuff I went through.”

More From XXL