Gang Starr’s ‘Hard To Earn’ And The Changing Face Of Brooklyn

Ed Note: The following is an essay remembering Gang Starr's classic album Hard To Earn, which celebrates its 20th anniversary tomorrow, March 8.

In the spring of 1994, Gang Starr’s booming system classic Hard To Earn was my favorite album. I played the first single, “Mass Appeal,” while throwing on my clubbing gear, I jammed the spooky “Code Of The Streets” while puffing blunts and blared the ghetto afro-futuristic “Tonz Of Gunz” through my walkman as I sat on the D train headed towards Brooklyn to hang with my crew at Frank’s. Coming out at a time when folks still called them streets Crooklyn, the seminal Hard To Earn represented those BK blocks when crack was still en vogue, Myrtle Avenue was known as Murder Avenue and dead bodies were occasionally found in Fort Greene Park.

Consisting of the late rapper Guru and producer/turntablist DJ Premier, the dynamic duo provided one of the most intense shattered glass soundtracks of the season. “Kids pullin’ triggers, niggas killin’ niggas, five-o sit and wait and tally death toll figures,” Guru proclaimed on “Tonz Of Gunz." With lyrics that could be as piercing as hollow-point bullets, he was both streetwise and literary. Although both Gang Starr members were out-of-towners—Guru hailed from Boston, Primo was outta Texas—they quickly shed their hick skins and submerged deeply into the murky waters of New York City hip-hop culture, and Hard To Earn was their brilliant manifesto of those times.

A week before Hard To Earn would celebrate its 20th anniversary, director Spike Lee spoke out on the ills of gentrification that have turned the streets of his native Brooklyn into, to quote the man himself, “the motherfuckin’ Westminster Dog Show,” where shaggy bearded hipsters and rail-thin girls sip their lattes in front of gleaming boutiques that were once grimy bodegas. Although brother Lee left those streets behind many years ago, he remembered a time when Brooklyn could be a simultaneously wild and inspiring landscape for young Black artists. Rock stars (Lenny Kravitz, Vernon Reid), writers (Carl Hancock Rux, Lisa Jones) and jazz musicians (Branford Marsalis, Steve Coleman) all populated the borough at one time as they climbed the ladder of success.

Yet there was also another element many of us old schoolers remember much too well from back then, a more dangerous component we often confronted on those sketchy streets. Too broke to be boheme, they still had big American dreams of “clocking dollars” and succeeding in the crazy world by any means. There were the Polo-clad Lo-Life street gangs, crack-slinging shorties, hoodie-wearing bad boys and posses strapped with gats. Dressed to kill, or perhaps just hurt, these were the boys that populated the night as they bought chicken wings at local Chinese joints, chilled on their stoops gulping 40s and hollered at the girls that switched pass them.

Some of them dudes came from broken homes and were already been behind bars before the age of 21. Others might’ve done well in school, but still weren’t sure how to input the master plan of escaping the harsh hustle of the hood. Meanwhile, in the back of a pissy housing project staircase, a posse banged out beats on concrete walls as their homeboys freestyled about their world in peril inside the projects.

It was that gritty world, as well as the diverse characters that populated it, that Gang Starr documented, both lyrically and sonically, with their eerie music. By 1994, having already released three studio albums, it was Hard To Earn that put them on the forefront of the then-emerging boom-bap movement in the mid-1990s. Primo was already one of the chief dirty boom-bap architects, contributing to KRS-One’s dope Return Of The Boom Bap, lacing the wondrousness of Jeru Da Damaja’s debut "Come Clean" and working on Nas’ instant classic Illmatic. By the time of Hard To Earn, he was more than ready to take things to the next level.

Assigned by the now-defunct Pulse Magazine to interview the group for a cover story, I’d spent most of March 8, 1994 tailing alongside Gang Starr as they did a radio interview at WBLS and an in-store at The Wiz on Broadway and 8th Street in Manhattan. Recording throughout much of the previous year at their personal music factory D and D Studios in midtown Manhattan, they were enjoying the admiration of their fans after months of isolating themselves in the lab.

“On this album,” Premier explained to me the day Hard To Earn was released. “I stayed as far away from jazz as possible. Right now, it’s all about hardcore. Right now, it’s about making real music for the kids in the street.” While other sound scientists—RZA, DJ Muggs, Mobb Deep, Pete Rock, Easy Mo Bee, Diamond D. and various others—were down with the new wave of boom-bap darkness that hovered over the music, nobody did it like DJ Premier.

“That’s the sound that identifies the streets, and the streets is what created hip-hop,” Primo continued. “That sound is urban and rugged, like it’s coming up out of the ground. With the music on Hard To Earn, I wanted to capture the vibe of the ghetto and what goes on there and the things that we’ve seen.”

As a writer, I was initially attracted to Guru’s lyricism as a well as his skills on the mic. As a wordsmith, his poetics on Hard To Earn were precise, while as an MC his voice was cool as a Blue Note album cover. Like a textual version of a Jamel Shabazz photograph, Guru’s words were snapshots of his journey from Boston to Brooklyn (“The Planet”), the stick-up kids he met hanging out on the streets of Bed-Stuy (“Code Of The Streets,” “Tonz Of Gunz”) and the struggles he went through (“The First Step,” “Mass Appeal”) before he became a champ MC.

“There are a lot of people who have gotten into this business because they were somebody’s friend or relative," Guru said about the album’s first single, “Mass Appeal." "It had nothing to do with them having any skills or paying dues. Nobody put me on; I had to get mine hard to earn.”

“For Hard To Earn, Guru gave me about forty song titles, and I picked the ones I thought were dope and catchy, and I could already imagine what I was going to do with the music," Premier said. "Guru doesn’t like to write until he has the music, but after I picked the titles, he and I would discuss them so I could form a picture in my mind of what the song should sound like.”

Like the old school turntable masters that he worshipped—Grand Wizard Theodore and Red Alert—the Texas-born homeboy could scratch his ass off. Listen to the brutal beauty of “Brainstorm” and “Speak Your Clout” to get a taste of this dying art form at its peak. “I bit a lot of Marley Marl’s style,” Primo said. “He had that lazy style, but it was so on. I always felt I was picking up where he left off.

“Guru also comes up with a lot of scratches, and I just do them,” he continued modestly. “We know how to bounce ideas off of one another, and just try to make the freshest music possible.”

Twenty years after its release, Hard To Earn still ranks high in a year that gave us such treasures as Illmatic, Ready To Die, Stress: The Extinction Agenda, Tical, Ill Commutation and Dare Iz A Darkside. Gone before his time, Guru died in 2010 from cancer at the age of 48, while Premier continues to do production for Joey Bada$$, Mack Wilds and others. Yet it's Maryland-based, Brooklyn-born rapper A-Boogie from StarVation who may have been able to sum up the album's effect best. “What Gang Starr did with rap music stood out from the crowd, which is what makes their records classics," he said. "The streets of Brooklyn might’ve changed, but Hard To Earn still sounds as rough and gritty as those streets were twenty years back.”

As with most brilliant albums, Hard To Earn hasn’t aged a day. —Michael Gonzales

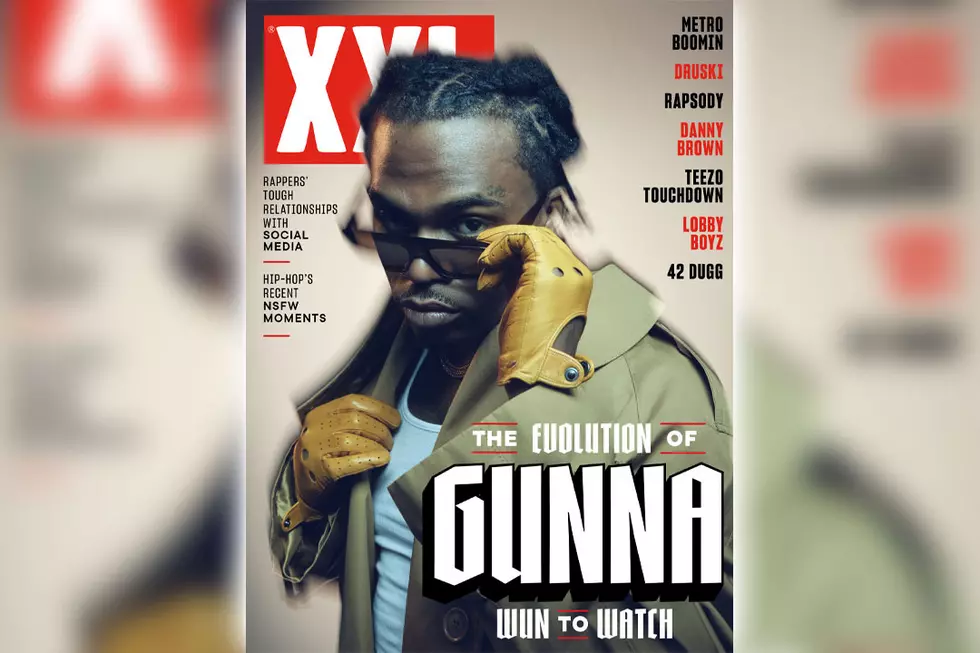

More From XXL