A Track By Track Breakdown Of ‘The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill’

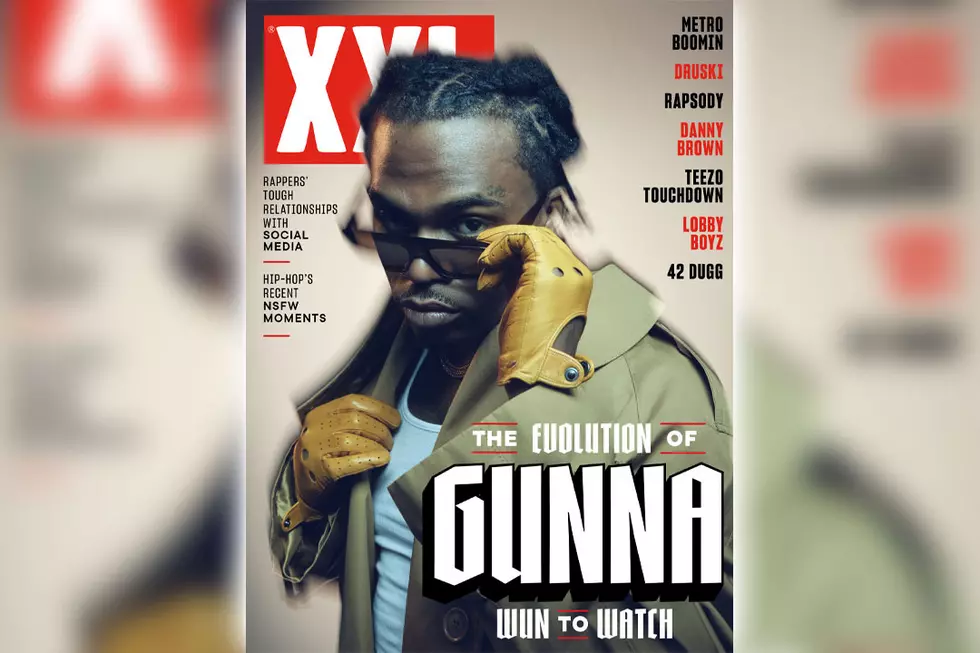

When The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was released on August 25, 1998, Lauryn Hill was 23 years old and pregnant with her second child, having experienced multi-platinum success, a world tour with The Fugees, and enough heartbreak to last a lifetime—or at least to span 14 tracks of a solo debut. Her studio band, New Ark—comprised of Vada Nobles, Rasheem "Kilo" Pugh, and twins Tejumold and Johari Newton, whom XXL spoke to extensively yesterday—was not much older. Together, the five of them would write the majority of a hip-hop classic, weaving reggae, funk, R&B and doo wop into an album that speaks as clearly today as it did on its release fifteen years ago.

During XXL's investigation into the album, Kilo and the Newton twins helped explain how each song was made, from the writing process to the recording to the genesis and execution of the ideas. But fifteen years is a long time, and with this album—especially with the writing and recording process so contentious throughout the years—some memories have been distorted by time, leading to a handful of contradictions; some songs may forever be in dispute. But to continue celebrating the album's fifteenth anniversary, XXL is letting some of the co-creators speak for themselves on what they remember of the making of the album.

Click through to see the stories behind each of these songs, and check out XXL's feature on Miseducation right here. —Dan Rys (@danrys)

"Intro"

Jo: That was Ras Baraka [beat poet and teacher from New Jersey]. Lauryn would have tapes [of the interludes], and we would play music under them. Ras Baraka's one of those beat poets, the early beat poets—he's now a principal. He was from Newark and was in a classroom with all of those kids. Those kids are probably about 30 years old now. [Laughs] We actually did a remake of that song—we were coming from the train station last night and heard it again. We did a big version of it, flipped it.

"Lost Ones"

Jo: We were in the place [in Jamaica] where Bob Marley created his music, in his house, which is a museum now. There's a studio that only Ziggy uses. So we were in there with the engineer, Errol Brown. Back then I was into a lot of weed smoking. We had this guy come around, and his name was Georgie—he lived in the back of the museum, he was a chef. He was like, "This is the same bong that Bob Marley smoked out of, take a hit." And I would take a hit. He would come every day—he called it The Chalice. Before we did "Lost Ones," he said, "Jo, The Chalice is ready!" and he handed [it] to me. And then Vada started doing the beat, and I started, [sings guitar part], and that was a song that, again, me and Lauryn came up with that.

Being from East Orange, you cannot escape dancehall reggae. So she was like, I wanted to do something [like that]. Everything was perfect, because it was over a beat that Vada did, and I came with the reggae—we were in Jamaica, so I wanted to make it reflect what we were doing. It wasn't typical reggae, because in reggae the chord moves, but for hip-hop's sake I kept it on one chord. It was an homage to KRS-One. The freedom of the album—if there's no more lyrics, let's sing a verse, sing, do a rap, sing—it was all about the timing, the type of artist we were working with.

Kilo: That was created right there in Bob's studio. The dope part was, my cousin, we call him Boom, he actually came up with the first part of that idea. He called me up and was like, "You guys gotta re-do that Boogie Down Productions [track] 'Supa Hoe'"—you know that hook, "Scott La Rock had 'em all"—and the drums, that was the beat, Scott La Rock. So I told Vada about that beat, and we were down in Jamaica creating one day, there it was. [Sings drum part] And then when you had the cuts in it, maaaaaaaan, it was crazy. So when Lauryn heard the beat, she was like, "Ahhh, this beat is hot," and she starts writing and rapping. Lauryn is the type where, in her immediate circle, she'll spit the verse and be like, "Yo what should I put right here? What should I put there?" I was like, "I was hopeless, now I'm on Hope Road," and she was like, "Ahh, that's dope, that's dope, I'll write it." So we were just throwing lines out there. She'd be writing and writing, and then she'd stop and ask us what we thought, and you'd be like, alright, try this, and we'd build it.

That song, in Jamaica she could not come up with a chorus for that song. We went from Jamaica all the way home, months and months and months, and she did like three or four choruses, and could not figure it out. Then we were in a studio in East Orange—my man has a studio there called Perfect Pair—and I walked in and I said, [Sings melody from chorus] and she was like, "That's it!" And that joint was crazy.

"Ex-Factor"

Tej: It was really our baby. We started in her attic in her guest house. That first session was weird, because she couldn't sing or something—she said the baby was doing something to her vocal cords. But the next week she got back to normal and started singing, and we just started playing. She also was doing this group called Edith's Wish that Clive [Davis] had signed to Arista. They had a demo where they were playing Jimi Hendrix's "Little Wing," and Lauryn was like, let's make a song for them. We were just playing around, and Lauryn said, "I got this idea." [Sings melody] So I was like okay, I think there's a B7 chord—

Jo: No one in hip-hop was using major seventh chords at that time, but that song was a hip-hop song.

Tej: So me and Jo was like, if we're doing this for Edith's Wish, let's put "Little Wing" in it, but let's do it in E flat. Lauryn started singing in her rock voice, "It could all be so simple..." you know, she went through the whole thing. We were like, you know, this is a good song for them. So we put it aside, started working on other things, but then that became "Ex-Factor." We laid "Ex-Factor" down, and I think it was either [Sony's] Donnie Einer came in, or Tommy Mottola, and he was like, "Lauryn, where's your work? It's time to do another Fugees album." She really wasn't feeling the Fugees right then.

Jo: So she said, ["Ex-Factor"] is my song, let's re-cut it, let's make it more hip-hop, let's put the "Cash Rules Everything Around Me" in it, she asked me to write a bassline for it—just make it work. We figured in our head it would be the ultimate combination of rap and R&B. She wrote some of the lyrics while she was on tour, and I would help her write some of the others. And it just came out—when Commissioner Gordon [engineer for the album] came in, he was like, "We gotta focus on one song at a time." So we just sat down, and he was like, "It needs a solo, it needs a guitar in it." And I knew how to do the "Little Wing" solo, and he was like, "Give me a guitar like that, and this is where the solo comes in." So I did it, and I was spent. He mixed it, and it sounded beautiful—you can't even hear the guitar in it until that point. Did it in one take. It was the only track me and [Tej] played on together.

Jo: Two-inch reels back then. We had Pro Tools, but [Lauryn] didn't want to use it. We did use it in the mix though, definitely used it in the mix. [Laughs] She came up with that part at the end—we actually introduced her to those [background singers], they were all church girls we knew from St. Paul's back in Newark, same church that Faith Evans went to. She already had the "Cry for me, cry for me, you said you'd die for me" part.

Kilo: Every instrument on the planet was in this booth—they had a harp in there. This dude came, he was a percussionist, he was making noises with everything. It was the most instruments I've ever seen in a session before.

"To Zion" (featuring Carlos Santana)

Jo: "Zion" is funny, because Lauryn and I were sitting in the kitchen at the big house, and she came in and was like, "This is what I was thinking in the shower. You know there's an African proverb that kids pick the parents that they come through? So I wrote this down." And I just said Lauryn, this is something that you must do, because me and Kilo tried to write a song about that and failed miserably. I was 24—I didn't have any thoughts about any children. So she told me she had been thinking about this for that beat, which was just a sample. And then we had real drums in there. She wrote "Zion" lyrically on her own; it was something that she needed to write.

Kilo: I did all the arrangements—the "marching, marching to Zion"—while she was in the booth. When she was in the booth singing the words, I was already creating the arrangements to go behind her words. When she finished one verse, I already had the backgrounds ready for that verse.

"Doo Wop (That Thing)"

Jo: The last few verses we were sparring—"Quick to shoot the semen/Stop acting like boys and be men"—I was coming up with lines like that. I would give her an idea—the rhythm I was concerned about, changing her rhythm. We just started painting pictures, just saying words that rhyme. Lauryn's really responsible for the way that one goes—she said she wanted to do a doo wop song. I was like, you wanna rap on that? Every song had a piece of Jamaica in it—every time you hear horns it was Jamaica, strings were probably New York. We sat down and did the majority at Chung King [Studio, in New York]. One night, I was like Lauryn, let's write a song about a pregnant girl, and she was like, "I don't know if I want to do that." She was like, why don't we talk about a friend, like a guy—"Remember he told you he was 'bout the Benjamins?"—and suddenly we just started adding to it, but we didn't have a hook. That thing. She was like, "Okay." We were looking for a single, and it turned out to be the first single. Every piece had a piece of Jamaica in it.

Kilo: We actually got it from a doo wop record. There was one song where the piano was really similar, and then the whole "Yeah yeah," all of that was just hot. And in Jamaica they had the live horns put on it. That's me singing—I'm the one that goes, [Sings] that real low note, all that in the background. That was fun.

"Superstar"

Jo: That was me and my brother's total collaboration as far as producers. She kinda had those chords, and it sounded weird to me. Then she put the clav on it, and I was like, this sounds like "Light My Fire." Every time, I would tell her that. And now I know what she was going for, but it sounded like "Light My Fire." All she was missing was that jazz riff. She was like "Okay," and added it in. I thought that was a smart idea if we could get the clearance. It was giving homage. I was a teenage kid who loved The Doors.

"Final Hour"

Jo: We wrote that over an Aretha Franklin break beat, and then she decided to get Premier to do the beat. But me and [Lauryn] wrote it.

Kilo: It had three different beats—we had all kinds of beats while she was doing "Final Hour." That was one of those songs that she was kind of piecing together raps, it came together with different raps. It wasn't just, let me sit down and write "Final Hour." She had several pieces of paper and she would just grab it and keep going. [Laughs]

"When It Hurts So Bad"

Jo: Yeah, that was mine. We did that in Jamaica, we did most of it in Jamaica. That was my baby—I directed it. That was kinda like my songwriting process back then, if I did something by myself that would have been what it sounded like. The keys and the bass on there were different. Lauryn sung on it and wrote a lot of the lyrics with me, but she kinda let me arrange it. That and "Everything Is Everything."

Tej: To me, that's Jo in a nutshell.

"I Used To Love Him" (featuring Mary J. Blige)

Kilo: I remember when they were making the beat in the attic [a studio in Hill's house]. Vada had this beat, and she was pacing in the attic, just saying these words. Some of the words that didn't get on the song were some of the most incredible words—some of the best words didn't even make the record. She was just singing out loud and humming this different stuff. It was incredible, it was definitely a vibe. That was probably one of the easiest records, there weren't as many instruments on it. It has a real jazzy groove, like that hip-hop jazz.

Jo: She wanted Mary on the album, 'cause Mary was her homegirl.

Tej: I hate this one the most. Didn't really like that one. I guess every album has that one song.

"Forgive Them Father"

Tej: That was my favorite song.

Jo: We were in Jamaica, and it had this sound to it. Ziggy's band played on it—we didn't really play on it, I just wrote the lyrics. A lot of these songs came from just going to a piano, and then Vada'd hear it, we'd add a swing to it. Then there was a lot of addition. It was that type of [thing].

Kilo: We was at the house, and they were working on the beat. I went to the store to get sandwiches, and I came up the staircase and she was writing a rap. I came in and I said, "Forgive the crowds, Lord, they know not why the sweat me"—I was singing Queen Latifah [from "Princess of the Posse"]—and she was like, "That's it—'Forgive them father for / they know not what they do.'" It was crazy. It was just little stuff that would trigger ideas.

"Every Ghetto, Every City"

Tej: It was written during the sessions, a track that I had written with Kilo, and then she changed the track and kept the lyrics. That's a song that Kilo helped her write lyrically. I actually wrote the chords to that. It's a derivative song, because she wrote the song to a track that I had done and then she replaced it. I forgot who she had play on it—Loris [Holland] I think, he added the clavs. That was in South Orange, in her childhood home, in the studio upstairs—I was actually on the piano playing some chords, and then she started to write to it, and then she recorded it in New York—it was those chords, but it didn't have that instrumentation on it, until Loris put the clavs on it.

"Nothing Even Matters" (featuring D'Angelo)

Jo: That was one of the songs that I really enjoyed the final version of. 'Cause I wrote it—I wasn't in the session when D [D'Angelo] was singing it.

Tej: I wrote the chorus. I think [D'Angelo's part] was done in London.

Jo: Yeah, and I wrote the lyrics. That was one of those songs I actually wrote in South Carolina [before the sessions started]—I had this beautiful Heritage guitar, one piece of wood, and I named it after a girl. I felt the girl betrayed me, so I sold it for an acoustic guitar, and I started writing songs. It's funny because I was like, "Nothing even matters," when people fall in love it should be nothing, the Earth should be in the middle of space, in this alternative world. [Lauryn] said okay. She said she was singing it in the shower. I had this song where I was talking about nothing matters—nothing. The concepts were always good, so we could go with the concepts. And then I heard D, and I was like, wow. The way D played on it too, wow. It was a song [Tej] wrote from end to end, and I wrote it lyrically.

Kilo: I know Tej played a lot on that, and I think James Poyser might've played a little bit on that song. We wrote the stuff right in her kitchen—we were sitting at the kitchen table, she's holding Zion, we got a big old-school radio sittin' in the corner. It was like a joke, you know what I mean? Nothing even matters. [Laughs]

Tej: At that time D'Angelo was my favorite artist, so I was like, wow. At the time I was kind of pissed at her because she didn't let me come into the studio [when D'Angelo recorded] to see, but I understand now, 'cause she kind of jacked him. It was one of those things where he was gonna sing on her album, and she was gonna sing on his without charging anything. She wanted a Donny Hathaway, "Closer I Get To You" type. So it was the perfect song for that. She wanted somebody who she respected—she tried to get Ben [Harper], but he was recording his [album] at that point. And that was weird, 'cause everyone and their mother wanted to get on this album.

"Everything Is Everything"

Jo: [Lauryn and I] wrote the first few bars together, and then we were under deadline, so we were in Sony's studios, and she was like, "Yo Jo, finish that." So I finished the rest of it, and we wrote the record together, the rapping part. And the second part—"Sometimes it seems / We'll touch that dream / Change comes slow or not at all"—it's like a rock rhythm. The songs [along with "When It Hurts So Bad"] are really personal to me, because I felt like if it wasn't all me, it was 85 percent me.

"The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill"

Tej: We wrote that, the two of us.

Jo: She told us she wanted us to write it.

Tej: It's a weird song, because every time she got a break, she was like, "Let's go over the song," and I was like, what song? We'd play it, and she'd go, "Sounds good, sounds good." Then four weeks later she'd say the same thing. By the end of the album it was done, but I wanted an intro on it, let me put something like Donny Hathaway on it. So I started to play it, and she wasn't happy with it—she was like, "I don't like the way you played that." I was like, what are you talking about? I wrote the song. And she said, "I'ma have to not let you play your own song that you wrote." So she got this guy Joe Wilson who was a gospel player. He came in and he was like, "What's wrong with this? This is good!" But Lauryn was like...it could've been something in her mind, but he just played it the same way. So then we had Loris Holland play on that. He's one of those cats that, if you just play something once, he'll just pick it up so quick. Like with James, it was nice, but with Loris if you played it one time, he got it. We had great musicians.

Jo: But the nuts and bolts of it were really me and T.

Kilo: That came from a song I originally wrote for Anthony Hamilton, and I had it in my writing pad. It said, "Fast is my world, it's spinning today / The time that has passed seems so far away." And she took my pad, and she was sitting down, and she said, "My world it moves so fast today / The past it seems so far away." She re-wrote the lines to that same exact song on the same piece of paper, right under it. She took the words from an Anthony Hamilton song, and I saw him and he just laughed about it, until later on when it was used as some proof [in the lawsuit].

More From XXL