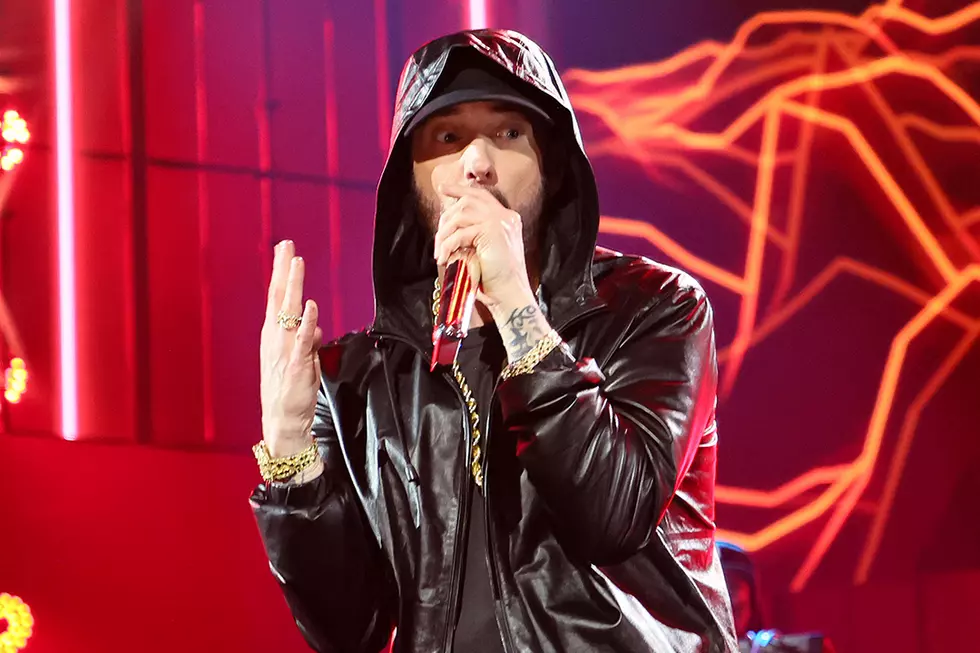

FEATURE: Pretty Fly For A White Guy

In the September 2003 issue of XXL magazine, we asked 25 rap artists to list their top five MCs. Only seven named Eminem. That’s more votes than Cassidy, Sadat X and Smoke from Field Mob got, but fewer than Biggie, Rakim, Tupac, Jay-Z and Nas. The results were something of an upset, considering that, at the time, Eminem was a global pop icon. He was both matinee idol and the original SoundScan Killer. The Slim Shady LP, The Marshall Mathers LP and The Eminem Show had already sold over 21 million albums, and his debut film, the semiautobiographical 8 Mile, had grossed $116 million domestically. The back of his baseball card was flawless.

Not impressed by statistics? He was also at, or at least very near, the top of the game in six stylistic categories: best flow, best wordplay, most controversial, wildest imagination, best storytelling (for “Stan” alone) and funniest album skits. Maybe his interviews could have been hotter. But by just about any conceivable measure, Marshall Mathers III was a legitimate candidate for the title of Best Rapper Alive. MTV2 thought so, ranking him third on their June 2003 22 Greatest MCs program, behind only Biggie and Tupac.

Which brings us back to that seven out of 25. Seven out of 25? Was his nasal voice that annoying? Were his drug references too explicit? His imagery too gory? His insults too childish? Or did it have nothing to do with tone or lyrics? Maybe it was something he had no control over. Like his skin color. And that, for better or worse, put him on a different playing field.

Do you remember the first time you heard Eminem? For me, it was early 1998, freshman year of college. The biggest rap nerd in the dorm had a new mixtape. I want to say it was a DJ A. Vee cassette. Yes, cassette, and Eminem was featured on two songs: Old World Disorder’s “3hree6ix5ive” (which was identified as “the underground shit that you did with Skam” on “Stan”) and Shabaam Sahdeeq’s “5 Star Generals.”

My first impression, however, wasn’t pure. Before Em’s verse came on, my friend revealed the big secret: “He’s White.” In retrospect, I was grading his performance on a curve. Sure, there were some good White rappers around, like El-P of Company Flow or Cage, but they weren’t even sniffing the mainstream. In 1998, rap fans—Black, White, everyone—were skeptical of White rappers. Eminem was no different. “I liked you/Thought you were okay for a White dude,” he’d say himself, of Everlast, on the 2000 diss record “I Remember—Dedication to Whitey Ford.”

For most people, the first time they heard Eminem was the same as the first time they saw Eminem. In early 1999, when the “My Name Is” video debuted on MTV’s Total Request Live, nobody could avoid his whiteness. The clip goofed on the issue, with Eminem playing dress-up as a Leave It to Beaver–like suburban dad, tacky talk-show host, chemistry teacher, Bill Clinton, Marilyn Manson, etc. He was obviously courting the TRL pop mainstream—okay, let’s just say it—White audience from the get-go. Remember, “My Name Is” was even mixed with AC/DC’s 1981 metal classic “Back in Black” and played on rock radio.

The song, video and AC/DC mash-up were greater reflections on White culture than Black culture. But does that mean Black people didn’t eat it up? Of course not. Eminem appealed to everybody. His subject matter was universal: broken home, dead-end jobs, drugs, the claustrophobia of the hood, the struggle with leaving it behind and, of course, baby-mama drama. Hip-hop accepted him. “In my opinion, it is not an issue,” said Jay-Z of Eminem’s whiteness, in the March 2003 issue of XXL. “I mean, he can rhyme. The guy’s got skills.” Nas chimed in with, “The dude lives, breathes, eats and shits hip-hop.”

But could a White guy be considered the best practitioner of an art form created by African-Americans?-Thomas Golianopoulos

For more of the Pretty Fly For A White Guy story, make sure to pick up XXL's June issue on newsstands now.

More From XXL