Indie vs. Major

Good News, Bad News

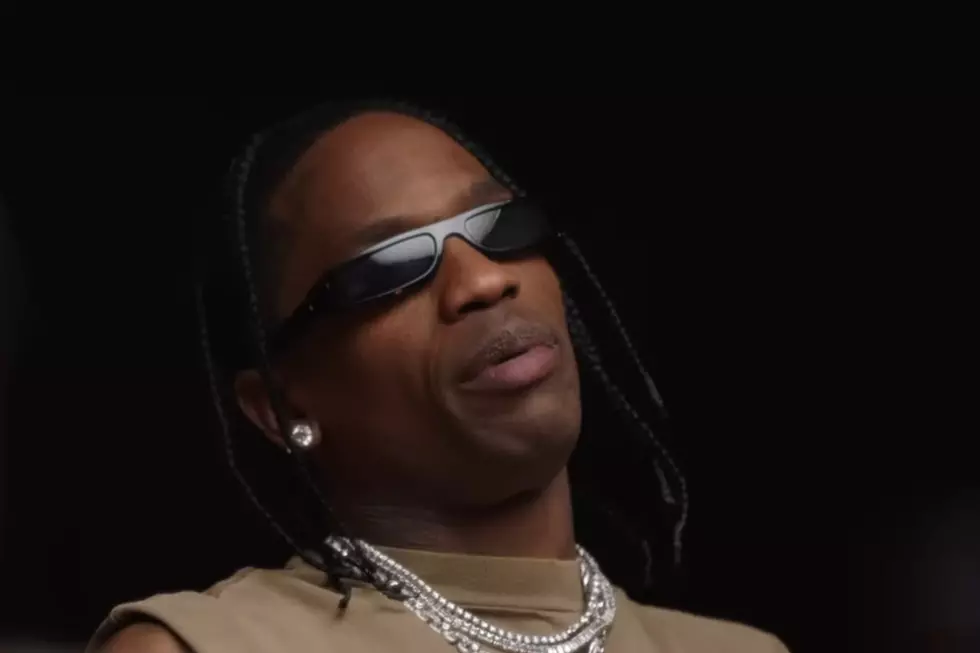

Late last year, two interesting things happened. Jim Jones’ third solo album, Hustler’s P.O.M.E., debuted at No. 6 on Billboard’s Top 200, having sold 106,000 copies its first week in record stores. Jones’ album was released by Koch Records, the New York–based independent label previously dismissed by 50 Cent as an “artists’ graveyard.” Six weeks earlier, Capitol Records, the venerable major-label home to the Beatles and the Beastie Boys, sold its iconic tower on Vine Street in Hollywood to a New York–based real estate developer. With album sales plummeting (Capitol’s 2006 releases included Hoodstar, the lowest-selling album of Chingy’s career), the 64-year-old company was badly in need of new income. (In January 2007, as sales of Jones’ album surged off the strength of his Top 5 pop single “We Fly High,” the announcement came that Capitol would merge with Virgin Records, another sign of parent company EMI’s ongoing financial troubles.)

The two events signified something artists and industry insiders have known for a while: This is a good time for independent labels, while major labels are struggling. (At 385,000 sold, Hustler’s P.O.M.E. has outperformed two recent G-Unit/Interscope releases: Lloyd Banks’ Rotten Apple and Mobb Deep’s Blood Money.) In an era of diminished album-sales expectations, the way independent labels operate is proving to be a more viable business model than that of the spendthrift majors. How did this happen? What are the indies doing right and the majors doing wrong? And what exactly is an independent label, anyway?

Billboard magazine, the industry-standard periodical that maintains official charts for sales and airplay, defines an independent label as one “not immediately affiliated to a larger corporate umbrella or ownership.” Billboard recently named Koch the nation’s “Top Independent Label” for the sixth straight year—Koch charted a total of 23 releases in 2006, a whopping 28 percent more than any other independent label. While the company releases everything from reissues of classic rock bands like the Kinks to the kiddie music of the Wiggles, its bread and butter is rap—the company made over $40 million last year in sales of rap titles alone.

“We were blessed to have radio hits this year,” says Alan Grunblatt, referring to Jones’ “We Fly High” and Atlanta rapper Unk’s “Walk It Out.” “We haven’t been that kind of company in the past. But Jim and Unk did great for us… The majors have so much overhead that they can’t make money off a record that sells 200,000. At Koch, we love that!”

A 42-year-old industry veteran, Grunblatt worked at Sony Music’s Relativity Records in the 1990s, making deals that gave regional labels like Houston’s Suave House and Memphis’ Hypnotize Minds national distribution. He understands the history of indie/major-label relations.

“In the beginning, rap music was really the exclusive domain of the independent labels,” says Grunblatt. “You had Jive, Tommy Boy, Profile, Def Jam. The majors didn’t want to get involved. They didn’t want to deal with that type of artist. They wanted only R&B. And it was great. Independent labels made a lot of money. Then, in the mid-’90s, the majors woke up, saw how big hip-hop was, and a feeding frenzy began.”

At the time, major labels leapt to license the entire output of successful independent labels. In 1996, No Limit signed a distribution deal with Priority, owned by EMI. Major label BMG began acquiring shares of Jive (a process completed in 2002, when they became outright owners of the label). In 1998, Universal Entertainment, the French-owned conglomerate that owns Interscope, A&M and Geffen, brought Def Jam into its empire. A year later, Cash Money signed on with a whopping $30 million pressing and distribution deal (a deal wherein Universal granted the nascent New Orleans label full ownership of its masters, a rare coup, and an 80 percent royalty rate on CD sales). Even the standard-bearer, the “Independent as Fuck!” Rawkus Records, attached itself to EMI, through Priority, in 1999.

At the height of the boom-time ’90s, it was not uncommon for a video to cost a million dollars or for a hot producer to get six figures for a single beat. Budgets across the board were overinflated, and as Grunblatt believes, “The majors destroyed the golden goose.”

The retail landscape of the music industry has changed drastically in the past year. CD sales are way down, while single downloads and ringtone sales are up. Tower Records, once the largest record-store chain in the United States, ceased operations in late 2006. Mom-and-pop record stores are closing everywhere, as large chains like Best Buy and Target can afford to undercut their prices. (Easier to offer a CD for cheap when some of the shoppers you lure into your store might buy a lawn mower too.)

Selling albums has become more difficult. And, simply put, the less a label spends on the making of an album, the fewer copies they have to sell in order to turn a profit. While Alan Grunblatt admits that the oft-mentioned figure of Koch artists making $7 or $8 per album sold is somewhat inflated (“That’s before money deducted for promotion and manufacturing costs,” he says), a smaller amount spent on promotion and marketing leaves more for an artist’s proceeds on the back end. (And artists like Jim Jones, who have their own promotion and marketing operations set up beforehand, can optimize such a situation.) Major labels have long operated on the premise that the more money spent making and promoting an album, the more money can be made selling it. That only works, however, when the public is buying.

South Bronx rap don Fat Joe is a good example of an artist who’s shown flexibility in the face of the faltering market. After watching his major-label releases’ sales slip, he decided to handle all the producing, marketing and publicizing of his music himself, under the auspices of his Terror Squad imprint, and in 2006, he signed a distribution-only deal with Virgin Records that grants him a higher percentage of profits and allows him to retain ownership rights of his master tapes, to boot. “I had to make sense of my career and figure out how I could benefit while not selling as much as the biggest niggas in the game,” says Joe, who last went platinum with 2001’s Jealous Ones Still Envy. “It’s a lot more work, no doubt about it. Very much more hands-on. Since I’ve been on an independent, I figured out that major labels are a bit sexier. They’ll put you in a nice hotel with your friends. You’re like, ‘Yeah, I’m at the Four Seasons with my people!’ But the truth is, you’re selling a million records and never seeing royalties. It’s more pampering, but it’s more of a stickup. It was a great look—I had my picture taken with some presidents—but God forbid I own my own masters.” (Spurred by the hit single “Make It Rain,” Joe’s latest album, Me, Myself and I, has sold 194,000 copies, and Joe says he’s made more money off it since its November release than he ever did from any of his previous efforts.)

In another sign of the shifting power dynamic, many major labels are breaking with the long-held convention of requiring that their artists record exclusively for them and are allowing the artists to sign side deals with indies. (While granting the artist greater financial freedom, this can serve as free publicity for the major, keeping their artists’ public profile high between releases—just like mixtapes.) Although he and his partner, Havoc, are signed to Interscope’s G-Unit, as the duo Mobb Deep, Queens MC Prodigy recently released his second solo album, Return of the Mac, on Koch. Similar deals allow Slim Thug, who’s signed to Geffen Records, and B.G., an Atlantic Records artist, to put out group projects—Slim Thug Presents Boss Hogg Outlawz: Serve & Collect and B.G. and the Chopper City Boyz: We Got This—both also through Koch.

In another sign of the shifting power dynamic, many major labels are breaking with the long-held convention of requiring that their artists record exclusively for them and are allowing the artists to sign side deals with indies. (While granting the artist greater financial freedom, this can serve as free publicity for the major, keeping their artists’ public profile high between releases—just like mixtapes.) Although he and his partner, Havoc, are signed to Interscope’s G-Unit, as the duo Mobb Deep, Queens MC Prodigy recently released his second solo album, Return of the Mac, on Koch. Similar deals allow Slim Thug, who’s signed to Geffen Records, and B.G., an Atlantic Records artist, to put out group projects—Slim Thug Presents Boss Hogg Outlawz: Serve & Collect and B.G. and the Chopper City Boyz: We Got This—both also through Koch.

B.G. presents an interesting case: a former major-label star who used success in the independent world to get back to the majors. After starting his career on Cash Money, where he sold millions of albums through the arrangement with Universal, the New Orleans rapper switched to Koch when his fortunes dipped. But last year, after releasing four money-making indie albums, he signed a new contract with major label Atlantic.

“When you’re on a major, you can get put in the public eye more,” B.G. says of his reasons for returning. “You can ask for more money when you doing shows.”

Read the rest of our Indie vs. Major feature in XXL’s July 2007 issue (#93)

Read the rest of our Indie vs. Major feature in XXL’s July 2007 issue (#93) More From XXL