New York Hip-Hop: Problem

“They’re sayin’ New York don’t hold down that slot no more/We ain’t makin’ people get up on the dance floor/We rhymin’ like other niggas, dressin’ like other niggas/Usin’ other niggas’ slang when that ain’t our thang/Niggas hate on us, learned about weight on us/Now they ready to skate on us.”

—Sadat X, “Back to New York”

Given the herd of iron horses that continually rumble through our city’s subway tunnels, you’d think we New Yorkers would be accustomed to the funky sensation of the ground moving underfoot. Yet recently, Gotham’s hip-hop community has been knocked off balance by a seismic tremor of a different kind: the recognition that rap’s national balance of power has shifted from NYC to all points OT. The evidence has been accumulating for more than a New York minute. While our friends from down South dominate the charts, many of our most respected homegrown artists (i.e. Fat Joe, Mobb Deep, Ghostface) couldn’t touch gold if they infiltrated Fort Knox. Symbolically, candy-painted whips, spinners, grillz (not fronts, mind you, there’s a difference) and big-bottomed exotic dancers—the signature vices and devices of hoods in current hip-hop hotbeds Atlanta, Memphis and Houston—have become the visual shorthand for anything rap-related, reducing the music’s public profile to a series of increasingly one-dimensional vignettes. Meanwhile, bloggers with attitude (those affiliated with the very publication you now palm, actually) have declared that a new holy trinity of rhyme titans—Atlanta’s Young Jeezy and T.I. and New Orleans’ Lil Wayne—has usurped the old Brooklyn-Queens triumvirate of Biggie, Jay-Z and Nas as the voices of choice for rap’s new generation. Sadly, the Rotten Apple has essentially become the “Forgotten Apple.”

It’s enough to sink any self-respecting New York hip-hop diehard (a category that includes this writer) into depression. Not because we’ve got it out for the South or any other region making noise across the map, but because, quite simply, we know what we like the most: cats spittin’ with some panache over none-too-polished, sample-driven breaks n’ beats. Count me among that hopelessly out-of-step faction that’s never sat through a Ludacris album from start to finish, that couldn’t tell DFB from D4L if our lives depended on it, and still thinks any mention of a rapper called “Tip” refers to a former member of A Tribe Called Quest. For us, New York—the birthplace of the last great music of the 20th century, ground zero for rap’s late-’80s golden era—will forever be synonymous with hip-hop. It’s like that, and that’s the way it is.

So it was with great anticipation that I eyed the local troops’ recent attempts to galvanize a full-fledged New York resurgence. Though the ever-outspoken Ghostface had taken to mocking D4L’s candy-sweet snap music smash “Laffy Taffy” in concert earlier this year, the real impetus arrived in the form of “New York Shit,” by none other than Busta Rhymes. Admittedly not the hugest Bussa-Bus booster myself, I never expected the old Dungeon Dragon to lead hip-hop in much of anything (save for number of costume changes per music video). But here he was, one of our own rap vets, dropping some unfashionably “real shit” that everyone with a New York allegiance, from indie purists Talib Kweli and Jean Grae to a rejuvenated DMX (apparently taking a break between car accidents) was jumping up to embrace and drop verses over. With producer DJ Scratch resuscitating the unforgettable ascending string loop from Diamond D’s early ’90s gem “I Went for Mine,” the song was both a joyous celebration of New York’s grand hip-hop heritage and an urgent demand to be taken seriously again on the national stage. Its throwback charm gave the young’ns a taste of two-turntables-and-a-microphone fundamentals, while warming the hearts of curmudgeonly folks, like yours truly, who still insist that the 1992 legal decision that forced producers to pay for sample clearances creatively hamstrung the art form when it had just begun. (Can I get a witness?) Busta had bestowed the New York faithful with a new anthem.

“New York Shit” then begat the Busta-hosted, DJs Green Lantern– and Kay Slay–manned On My New York Shit mixtape—a showcase of the five boroughs’ finest vocal talent, both established and up-and-coming, and the local rap community’s biggest display of collective civic pride since Do Wop’s landmark ’95 Live. But while On My New York Shit should have been a moment of triumph—a resounding confirmation that you should never sleep on The City That Never Sleeps—the impact felt more like a temporary high. Despite a healthy offering of adrenaline-inducing fare (Papoose’s “Out in NY”; Maino’s “Bed Stuy Anthem”; JR Writer spitting over the “Bridge Is Over” instro; Jae Millz’s offhand assertion that competition is “softer than a hamburger bun in the Hudson”), there was also plenty of filler (much of the mix’s final third), and a few outright disappointments (an asthmatic-sounding Lloyd Banks on “My House”; a posse cut featuring Ghostface, Kool G Rap, Raekwon, Lord Tariq and Big Daddy Kane that somehow managed to be boring). Much as my heart might have wanted to, my big-city cynicism wouldn’t let me buy into these festivities. At least not without a wary ear. The real questions and issues facing NYC’s status in the game were still out there and needed to be addressed. Specifically...

Here in 2006, what the hell is New York hip-hop supposed to sound like, anyway?

Any aficionado could tell you what prototypical New York hip-hop sounded like in the early ’80s: Bronx pioneers bragging and harmonizing over disco-funk rhythms. The mid-’80s: hard rappers rhyming over even harder drum machines. Late-’80s: Five Percent science and James Brown loops. Early ’90s: jazzy stand-up bass samples, reverb-soaked horns and shouted choruses (a.k.a. “Carhartt Rap”). And mid-’90s: QB, Premier productions, Wu-Tang. But since then, it’s pretty much been a free-for-all.

Essentially, New York hip-hop stopped meaning “real hip-hop” in the minds of devoted rap fans the moment Puff fell off his motorcycle and started tap-splashing through puddles. It’s understandable. As rap emerged as the dominant youth music worldwide, labels like Bad Boy, Roc-A-Fella, Ruff Ryders and Murder Inc. kept New York relevant by churning out hits of varying quality that appealed to the genre’s expanding fan base. Yes, New Yorkers are a business-savvy bunch (the cost of living here is too damn high for us not to be). But does the fact that our boom-time representatives opened the commercial floodgates years ago mean today’s New York rap dudes get a free pass to make records that sound a whole lot like the ticky-tacky shit they simultaneously accuse of ruining rap? Consider any number of questionable singles from the past year or two from hometown heroes: Cam’ron’s abominable Cyndi Lauper–sampled “Girls,” Fat Joe’s ill-advised Nelly duet “Get It Poppin,” Remy Ma’s “Whuteva”—an aural train wreck that outdoes the cacophony of anything ever produced below the Mason-Dixon Line. And yes, Busta himself, who with every radio spin of his will.i.am-helmed clunker “I Love My Bitch” is wiping out the goodwill created by “New York Shit.” Short of making ’em snap to this, our peeps have exhibited some pretty poor taste lately.

Add in Dipset’s throw-everything-at-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks philosophy (which encompasses a song called “Crunk Muzik,” which doesn’t actually sound much like crunk music, and remakes of material by Master P, Salt ’N Pepa and Jefferson Starship) and a marginalized set of veterans (Ghost, Rae, AZ, Sadat X, Pete Rock, Preem) trying to right the ship by making tracks the old-fashioned way, and you’ve stumbled on the real conundrum. How can anyone hope to revive New York hip-hop when there are a million and one ideas out there as to what New York hip-hop really is? This isn’t a celebration of diversity. This is, as EPMD used to say, total chaos and mass confusion. I know the cure-all explanation is that anything by New York cats that’s hot is New York hip-hop. But the “New York Movement,” as Busta calls it, would probably benefit from an ounce of aesthetic cohesion.

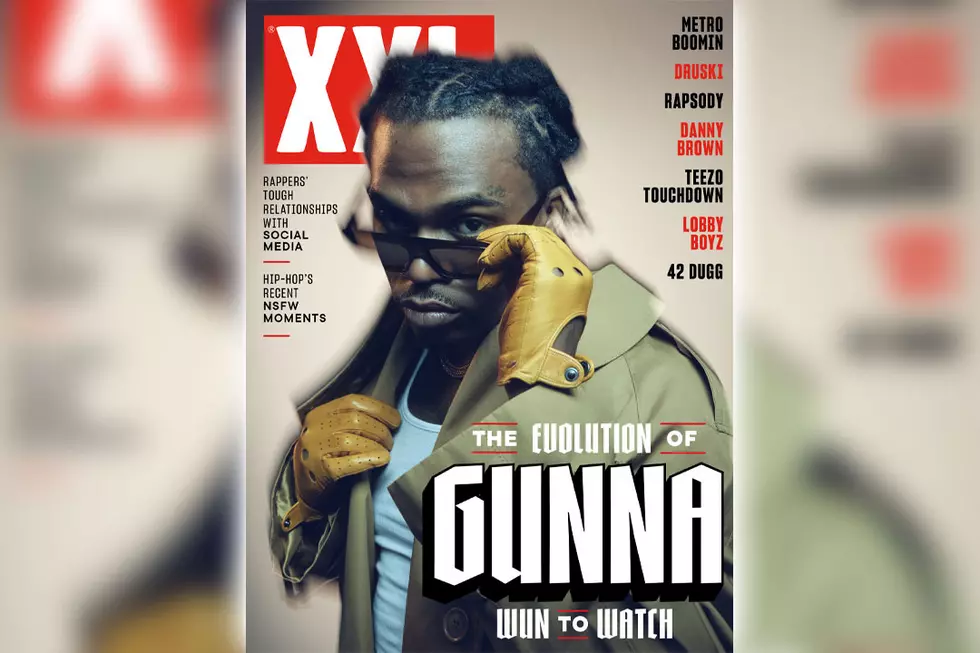

Read the rest of this feature in the September 2006 issue of XXL (#84).

More From XXL